Perfect Pairing

June 30 – September 29, 2022The Audubon Room | Hatcher Library Gallery

|

A Perfect Pairing of Cookbooks and Dinnerware

A dozen selections from the stellar collection of the Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive at the University of Michigan Library Special Collections Resource Center have been perfectly paired with delicious dishes from the International Museum of Dinnerware Design to make a feast for the eyes.

A “perfect pairing” usually refers to a taste compatibility between wine and a food group, such as wine and cheese. For example, some believe a perfect pairing would be Cabernet with duck confit and turnips or Pinot Noir with bison rib eye steaks and roasted garlic — wines with sauces, spicy food, hors d’oeurvres, etc. But other things can be perfectly paired, such as fruit and cheese, a couple, or a clothing selection. Sometimes pairs are made more perfect when they are catalysts for the imagination. That is what the curators are serving in A Perfect Pairing of Cookbooks and Dinnerware. The intention is to nudge the viewer to think beyond the first logical choice.

Of course, cookbooks and dinnerware both feature the interaction of food and people. Dining brings together diverse communities. Cookbooks provide people with the recipes and stimulate creative food adventures. Dinnerware and its dish, glass, and utensil components are the functional, utilitarian objects that allow one to enjoy the food one makes with the recipes in cookbooks. People select both cookbooks and dinnerware with intention. The right ingredients along with an inspired recipe create a delicious and beautiful meal that is enhanced when the cuisine is presented on a thoughtfully curated table setting.

Bon Appetit!

Juli McLoone, Curator, University of Michigan Library, Special Collections Research Center

Margaret Carney, Ph.D., Director, International Museum of Dinnerware Design

Exhibit curators

June 2022

Acknowledgments

Randal Stegmeyer and Margaret Carney took the photographs. Brooke Murphy, Jeff Gilboe, Jess Ortegon, and Shannon Zachary provided support in the making of this exhibit.

The International Museum of Dinnerware Design

The International Museum of Dinnerware Design (IMoDD) was established in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in 2012 with the knowledge that dining is a shared experience that can bridge together different communities. It is the only museum in the world dedicated to celebrating dining. While conceptually an art museum, a food-centric celebration of dining has been a key feature since its inception.

IMoDD celebrates a significant aspect of our daily lives. The permanent collection of more than nine thousand objects features international dinnerware from ancient to futuristic, created from ceramic, glass, metal, plastic, lacquer, fiber, paper, wood, and more. The collections include functional dinnerware, fine art referencing dinnerware, and a bit of kitsch thrown in for good measure. Research on the collection is augmented by a library and related archives comprised of dining-related advertisements, photographs, and design sketches — including original design renderings by the industrial designer Viktor Schreckengost.

The museum collects, preserves, and celebrates masterpieces of the tabletop genre created by leading artists and designers worldwide. Through its collections, exhibitions, and educational programming, it provides a window on the varied cultural and societal attitudes towards food and dining and commemorates the objects that exalt and venerate the dining experience.

The Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive

The Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive (JBLCA) brings together a diverse body of materials documenting the production, promotion, preparation, and consumption of food and drink, with a particular focus on American culinary history. The collection originated with the donation of a rich assemblage of cookbooks, menus, and other material by culinary historian and adjunct curator Janice B. Longone and her husband, University of Michigan professor emeritus Daniel T. Longone. Additional purchases and contributions from other donors have continued to strengthen the collection, which serves scholars, students, and everyone with an interest in exploring the roles of food and drink in society.

Today JBLCA encompasses materials dating from the sixteenth to the twenty-first centuries and includes cookbooks for national and international markets, regional and immigrant cookbooks, charity cookbooks, household management and etiquette guides, advertising ephemera, and restaurant menus, as well as handwritten family recipe books and culinary artifacts. Materials like these offer a window into how readers, diners, and cooks of the past saw themselves, their neighbors, and their larger communities. Through the documentary record one can explore not only the availability and frequency of foodstuffs and cooking technologies, but also the advent of new technologies and food system industrialization; changing attitudes towards diet and health, moral and aesthetic arguments surrounding homemaking and child-rearing; and shifting intersections of race, class, and gender.

JBLCA is a collection in the University of Michigan Library’s Special Collections Research Center.

1a

In more than 250 years of manufacturing, Wedgwood invented seemingly endless types of dinnerware in terms of clays, glazes, decorations, forms, and on and on. There seems to be nothing they didn’t try and then succeed in marketing to the public. Sometimes necessity is the mother of invention. Between 1795 and 1805 there were economical upheavals and flour shortages experienced in England during the Napoleonic Wars. While Josiah Wedgwood had created caneware in the 1770s, it was during this time of flour shortage that he created caneware game pie and pastry dishes. A game pie is a form of meat pie that features partridge, pheasant, deer, and hare. If even the wealthy couldn’t afford a flour-based pastry, his invention gave the illusion those delicacies were still being served. The game pie dishes were made of ornate caneware, which resembled a flour crust. There was a ceramic insert that actually held the rice and stewed meats. The caneware “pastry” exterior was topped with finials, such as game birds and rabbits, to emulate the lavish pastries people loved. This caneware body could handle the oven heat and embellish any dining table it graced.

1b

| Maria Eliza Ketelby Rundell. A New System of Domestic Cookery; Formed Upon Principles of Economy and Adapted to the Use of Private Families. A Edition, Corrected. London: Printed by S. Hamilton for J. Murray, 1813. The Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive. Gift of Janice Bluestein Longone. |

After being widowed in 1795, Maria Eliza Ketelby Rundell began systematically collecting recipes and household tips for her daughters, eventually culminating in the publication of Domestic Cookery in 1806. In addition to recipes, Rundell offers advice on servants, household accounts, and planning menus for genteel households. The book was an instant success and appeared in several dozen editions over the nineteenth century.

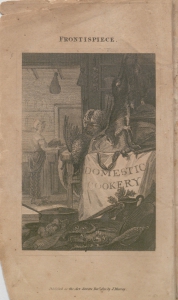

The engraved frontispiece of this 1813 edition shows a woman in a Georgian-era kitchen carrying a large slab of something, perhaps cheese or meat, on a platter. Bags that might contain dried herbs and a rabbit carcass hang from the walls and ceiling. An enormous head of cabbage, a pheasant, and sausages cascade over the table, while in the foreground, fish lie atop pots and sieves. Altogether, the image promises a life of rich abundance.

The chapter on “Savoury Pies” provides a wide array of pastry-and-meat combinations that could transform those rabbits and pheasants into a feast fit, if not for a king, at least for a respectable, genteel family. Of particular interest is Green-Goose Pie, which seems to reference a possible lack of flour, as it reads, “bake them either with or without crust; if the latter, a cover to the dish must fit close to keep in the steam.”

Partridge Pie in a Dish

Pick and singe four partridges; cut off the legs at the knee; season with pepper, salt, chopped parsley, thyme, and mushrooms. Lay a veal-steak, and a slice of ham, at the bottom of the dish; put the partridge in, and half a pint of good broth. Put puff paste on the ledge of the dish, and cover with the same; brush it over with egg, and bake an hour.

2a

Few sets of dinnerware that are 184 years old are as well-documented as this set, which, in total, is comprised of forty-one pieces. A number of pieces have been mended and survive with the set because this was such an heirloom for family members. While much is known of the family history, it is most interesting that this English dinnerware set was purchased in 1838 by Samuel and Mary Fitzwater when they moved to Beech Flats, Pennsylvania, built a lumber camp, and “hired many men to help in the lumber business which was the beginning of that area development.” They purchased two sets, and that may be why so many pieces still remain. The set was authenticated in the 1970s by the Smithsonian Institution’s curator of ceramics and glass, Paul V. Gardner. There is little of this dinnerware from this manufacturer and era still in existence. The pattern is referred to as Kyber.

2b

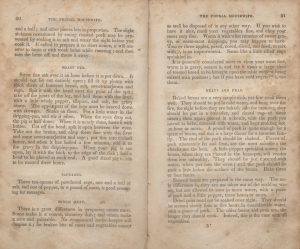

| Lydia Maria Child. The American Frugal Housewife: Dedicated to Those Who Are Not Ashamed of Economy. 22nd Edition. New York: Samuel S. & William Wood, 1838. The Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive. |

Lydia Maria Child, author of two bestselling novels in the 1820s, married lawyer and abolitionist David Lee Child in 1828. While their marriage was affectionate, her husband was not an effective breadwinner, and Lydia Maria Child felt intense pressure both to earn money and to run their household with the greatest economy.

Drawing on her own experiences, Child published The Frugal Housewife in 1829, offering a window into the multitude of mundane, laborious, but essential tasks that fell to women: feeding pigs, preserving meats, tracking use of linen, ensuring vegetables lasted through the winter, and cooking nourishing meals with limited tools. Child’s book was immensely popular, perhaps reflecting the growing geographic and financial mobility of the time. A woman might be far away from family, or she might be reluctant to ask for advice after falling on hard times, perhaps ashamed that she needed to learn to do tasks formerly carried out by hired help.

Despite the success of The Frugal Housewife, the Childs continued to struggle financially. When Lydia Maria Child published her first explicitly anti-slavery text in 1833, An Appeal in Favor of that Class of Americans Called Africans, she was ostracized from Boston high society and her children’s magazine, Juvenile Miscellany, collapsed. Nonetheless, Child continued her anti-slavery work, became editor of The Anti-Slavery Standard in 1841, and in 1860 wrote the introduction to Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl.

Beans and Peas

Baked beans are a very simple dish, yet few cook them well. They should be put in cold water, and hung over the fire, the night before they are baked. In the morning, they should be put in a colander, and rinsed two or three times; then again placed in a kettle, with the pork you intend to bake, covered with water, and kept scalding hot an hour or more. A pound of pork is quite enough for a quart of beans, and that is a large dinner for a common family. The rind of the pork should be slashed. Pieces of pork alternately fat and lean are the most suitable; the cheeks are the best. A little pepper sprinkled among the beans, when they are placed in the bean-pot, will render them less unhealthy. They should be just covered with water, when put into the oven; and the pork should be sunk a little below the surface of the beans. Bake three or four hours.

3a

While Meadow Visitor is not an uncommon pattern for French Haviland Limoges china circa 1876–1886, this particular set was definitely custom designed. Quite often the pattern includes butterflies, while this set, commissioned by Henrietta and Magnus Butzel for their wedding in 1869, features a vivid pink ground with birds and elaborately braided handles on serving pieces. And, most significantly, nearly every piece bears the signature inscription of “Magnus and Henrietta Butzel” in gold script.The designer, Henri Léon Pallandre, was a noted Parisian flower painter, and this set is decorated utilizing a combination of transfer and hand-painting. Donated to the International Museum of Dinnerware Design by the great-grandchildren of the Butzels, this heirloom set was always considered to be the Butzel’s wedding china, even though it wasn’t (according to the backstamps) manufactured until around 1879, ten years after their wedding. They wouldn’t have been the first couple to select their “wedding china” after the actual event, and a set of this size would have taken a long while to be created. According to family history Magnus Butzel was an early Detroit businessman and supporter of the Jewish community. His company provided Civil War uniforms to Union soldiers and was active in the Underground Railroad. He was also an early advocate for public libraries. When Henrietta died in 1928, the china was passed on to their son, Michigan Supreme Court Justice Henry Magnus Butzel, and his wife Mae (grandparents of the donors Mary, Judy and Dick). It is a miracle and a credit to the Butzel family, that seventy-seven pieces survived 142 years with virtually no cracks or chips.

3b

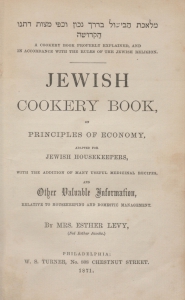

| Esther Levy. Jewish Cookery Book: On Principles of Economy, Adapted for Jewish Housekeepers, with the Addition of Many Useful Medicinal Recipes and Other Valuable Information Relative to Housekeeping and Domestic Management. Philadelphia: W. S. Turner, 1871. The Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive. Purchased from the Trust Fund of Lathrop Colgate Harper. |

Esther Levy’s 1871 Jewish Cookery Book was the first Jewish cookbook printed in America. Levy, an English immigrant to Philadelphia, presents an entirely kosher menu, emphatically stating in her preface that, “without violating the precepts of our religion, a table can be spread, which will satisfy the appetites of the most fastidious.” Levy draws her recipes from a wide net: English trifle keeps company with American okra soup, German-inspired matzo cleis with ginger and nutmeg, and Sephardic-influenced roast veal with olive oil and lemons.

Jewish Cookery provides guidance on every aspect of successful housekeeping, from daily management of servants, to orchestrating the meticulous household cleaning required before Passover, to arranging elaborate dinners complete with finger glasses, wine and champagne, candelabra, and flowers. Levy was writing for a generation of upwardly mobile Jewish women wishing to balance religious observation with the need to meet the formal expectations of sophisticated society. As a result of industrialization and urbanization, the number of households employing servants increased dramatically between 1870 and 1910. Even at the beginning of this time period, aspirational households in Jewish cultural centers like Philadelphia would have employed domestic help, frequently immigrants from Ireland, Central Europe, and Scandinavia. Scholar Eileen Solomon argues that in this context, Jewish Cookery’s didactic tone and detailed instructions provided reassurance and confidence to both housewife and servant that they could fulfill the expectations of the new roles they inhabited as they traveled geographically and socio-economically.

Queen Cakes

Mix a pound of dried flour with a pound of sifted sugar and some currants; wash a pound of butter in some rose water; beat it well, then mix with it eight eggs, yolks and whites, separately; put in the dry ingredients by degrees; beat the whole an hour; butter little tins, teacups, or saucers; have them only half full with the batter, and bake. Sift a little fine sugar over as you place them in the oven.

4a

Literally hundreds of different dishes, glasses, and utensils have been created over the centuries that have very specific functions. One of these is “the celery.” However, the shape of the piece that is designed to hold celery on the table during family dining has evolved from the nineteenth century, when it was frequently a glass vase form intended to hold an entire head of celery upright. It was a rather ostentatious way to present celery on the table. Celery was often served fresh between courses in the Victorian tradition. In the nineteenth century it was a status food that only wealthy families could afford. During the twentieth century “the celery” became an oblong serving dish which recognized its diminished role as a prestige item on the table. Later celery was a popular restaurant menu item, but only up until about 1950. Now “the celery” has virtually disappeared as a serving piece option.When a head of fresh celery is placed in this Rose Sprig pattern American pressed Vaseline glass celery vase, the vivid uranium glass presents the celery to all diners in a rather magnificent manner.

4b

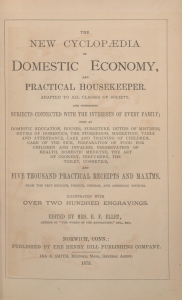

| Elizabeth Fries Ellet. The New Cyclopaedia of Domestic Economy, and Practical Housekeeper. Norwich, Connecticut: The Henry Bill Publishing Company, 1873. The Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive. Gift of Janice Bluestein Longone. |

The frontispiece of The New Cyclopaedia depicts a well-dressed white family at table. While the celery vase is not ornate, this trendy vegetable is displayed upright next to the roast poultry on the right. In the background, a Black woman carries additional dishes to the table on a tray. While no descriptive text accompanies the frontispiece, the illustration reflects structural divisions of the time. Regardless of race, a woman in 1870 was more likely to be a servant than to manage servants. However, even after the Civil War and emancipation, Black women in particular often found domestic service the only means of earning money open to them. This illustration is a reminder that in household guides of this period there is often a distinction between the presumed reader and the presumed cook or general maid who would do the work.Elizabeth Fries Ellet (prolific author and granddaughter of Revolutionary War captain John Maxwell) writes from and for the housewife’s perspective, expressing little sympathy for servants. She declares, “The greatest trouble in housekeeping is the difficulty of procuring and retaining good servants,” for Americans “will prefer any hardship or privation” to service, while Irish and German emigrants “have to be taught every thing” and are at risk of being “corrupted by intercourse with other servants.” Reluctantly acknowledging that employers must offer some inducement, Fries Ellet suggests organizing housework so as to “leave a portion of the day for the girl’s own time, which she is at liberty to employ as she pleases.”

To Stew Celery

Wash the heads, and strip off their outer leaves; either halve or leave them whole, according to their size, and cut them into length of four inches. Put into a stewpan with a cup of broth or weak white gravy; stew till tender; then add two spoonfuls of cream, a little flour and butter, seasoned with pepper, salt, nutmeg, and a little pounded white sugar; and simmer all together.

5a

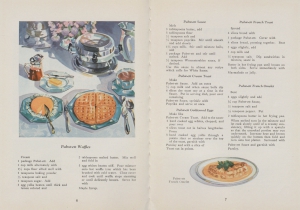

These exuberant and striking Art Deco design breakfast pieces — a syrup server, batter bowl, and waffle iron — were manufactured at the Robeson Rochester Corporation in Rochester, New York, known for their manufacturing of kitchen appliances, and marketed under their trade name of Royal Rochester. The rare design pattern for this line was named Modernistic. The ceramic pieces were produced and hand-painted in Ohio at The Fraunfelter China Company.There are a few other pieces that may accompany this breakfast set — a large coffee samovar, an electric percolator, a teapot, cream and sugar, small cups in metal holders, a lidded casserole in a chrome metal stand, and a pie plate. There was a ladle, too, that went with the batter bowl, but so few have survived that there aren’t even photographs available of any in public collections. The Modernistic pattern made its debut in the Christmas season of 1928, when the general public was not yet accustomed to the Art Deco style. It was a marketing failure and by Christmas season 1929 it was notably absent. Thus these Modernistic breakfast items are extremely rare and highly prized.

5b

| Alice Bradley. Breakfast to Midnight, Recipes with Pabst-ett. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Pabst Corp., 1929. The Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive. Gift of Janice Bluestein Longone. |

You may recognize Pabst as the brewer of Pabst Blue Ribbon lager, but what are Pabst-ett waffles? And why was a Milwaukee brewer marketing Pabst-ett to 1920s housewives as the perfect snack food and baking ingredient for any time of day and night?

Pabst Brewing Company was one of the most successful breweries in America in the late nineteenth century. In 1907, a promotional pamphlet advertised their plant’s capacity to produce sixty-two million gallons of beer each year. However, when Prohibition came into effect in 1920, banning the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors, Pabst and other breweries had to change course to survive. Many turned to near beer (0.5% alcoholic drinks), malted milk, and soda, but more surprising ventures included Coors’s ceramics, Yuengling’s ice cream, and Pabst’s cheese.

Pabst-ett was a soft, spreadable cheese similar to Velveeta, marketed as “a thrilling food with a vivid personality” that could be added to anything from salad loaf to chocolate cake. Testimonials printed at the back of this 1929 recipe booklet praise Pabst-ett for “being so easily digested that even the youngest of children can eat it,” and as “the one food in our household which everyone likes.” By 1930 Pabst had sold more than eight million pounds of cheese. When Prohibition ended in December 1933, however, the brewing company returned to the beer business. Pabst-ett was acquired by Kraft, but soon faded from both markets and popular memory.

Pabst-ett Waffles

Cream: 1 package Pabst-ett.

Add: 1 cup milk alternately with

1 ½ cups flour sifted well with

3 teaspoons baking powder

½ teaspoon sugar. Add

3 egg yolks beaten until thick and lemon colored and

2 tablespoons melted butter. Mix well and fold in

3 egg whites beaten stiff. Pour mixture onto hot waffle iron which has been brushed with cold water. Close cover and cook until waffle stops steaming or until delicately brown. Serve hot with

Maple syrup.

6a

Homer Laughlin has been making Fiesta almost continually since 1936. One of the things that makes the original colors unique is the brilliance of the orange/red glaze. Uranium in the glaze makes it so vibrant. That color was discontinued in 1942 because uranium was needed for the atom bomb. A Geiger counter placed next to the orange glazed pieces today registers so much radioactivity that one should be discouraged from filling a cup with acidic beverages such as coffee, tea, orange juice, or tomato juice. The current glazes in the newer Fiesta are all safe to use.

6b

| Women’s City Club of Oakland and the East Bay. Dee-licious Recipes. Berkeley, California: The Professional Press, 1932. The Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive. Gift of Janice Bluestein Longone. |

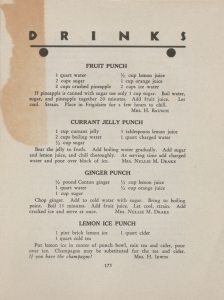

Popular in the 1920s and 30s, the Art Deco style is characterized by stylized or geometrical forms in bright colors. The Fiestaware on display in this case exemplifies the style through its colors and concentric rings. Art Deco influence can also be seen in the cover design of this 1932 cookbook published by the Women’s City Club of Oakland and the East Bay. Black geometric rays — echoing the sunrise motif popular in Art Deco — point upward to frame the silhouette of a woman dining in a stylized floral print dress, with octagonal artwork on the wall behind her. Cookbooks such Dee-licious Recipes were often produced by women’s groups in the early to mid-twentieth century, often as a way to raise funds for a charitable cause or for the organization’s general needs. While this cookbook does not specify a particular purpose, the fundraising goal is evident in the numerous advertisements from businesses, such as Bess Riner Beauty Shop, Mildred Miller Bridge Classes, and Oakland California Towel and Linen Supply. While an editorial committee assembled the book, dozens of members contributed recipes, from Mrs. J. De Ferria’s Quince Honey to Mrs. B. P. Keys’s Pineapple Lemon Pie to Mrs. L. F. Traver’s Booze Cake. Notably, Booze Cake calls for liquid from raisins soaked in water, but leaves out the usual bourbon, presumably because Prohibition was still in effect when this book was published in 1932.

Lemon Ice Punch

1 pint brick lemon ice

1 quart cold tea

1 quart ciderPut lemon ice in center of punch bowl, mix tea and cider, pour over ice. Champagne may be substituted for the tea and cider. If you have the champagne! Mrs. H. Irwin.

7a

The Dionne Quintuplets were five identical girl babies born on May 28, 1934, in Callander, Ontario, Canada. They are the first identical quintuplets known to have survived their infancy. Cécile, Émilie, Annette, Marie, and Yvonne lived at a hospital that became a tourist site called “Quintland” for the first several years of their lives. After a custody battle, the quintuplets moved back with their parents. In 1998, the province formally apologized to the surviving siblings and a compensation settlement was agreed on. Cécile and Annette are now in their late 80s. The entire fiasco has become emblematic for children’s rights.There are Dionne Quintuplets souvenir dolls, calendars, lamps, and even dinnerware. Several companies were selected to nourish the children, including Quaker Oats. These product placements served as endorsements in the eyes of the company as well as the public. This six-inch diameter chrome cereal bowl was available through the mail from Quaker Oats as a premium on their first birthday. It has the faces of each girl in repoussé in the center of the bowl and their names in script adorn the rim. One only had to send in two Quaker trademarks and 15 cents to cover postage and handling fees.The Dionne Quintuplets were featured in a number of additional advertising campaigns. The silver-plated spoons were made for the Palmolive Soap Company, which sold them for 10 cents and a couple of labels from Palmolive products. Tens of thousands of the spoons were produced.

7b

| Ladies Home Journal, November 1937. The Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive. |

As the first documented quintuplets to all survive infancy, the Dionne sisters — Yvonne, Annette, Cécile, Émilie, and Marie — were the focus of much media attention throughout their childhood. During the years that they spent in the custody of the province of Ontario, they lived on public display. “Quintland” became one of the biggest tourist attractions in Ontario, with approximately three million visitors between 1934 and 1943. Additionally, the girls’ names and images were used to advertise numerous products to a public fascinated by their existence. Many such product advertisements appeared in Ladies Home Journal, a popular American women’s magazine in the early twentieth century. Paging through the issues of 1937 reveals illustrations of chubby toddlers with dark curls and smiles accompanying advertisements extolling the benefits of Colgate toothpaste, Palmolive soap, and Karo syrup:“five famous smiles kept bright and sparkling with Colgate dental cream” “Growing lovelier day by day … The Dionne Quins use only Palmolive” “Karo is the only syrup served to the Dionne Quintuplets. Its maltose and dextrose are ideal carbohydrates for growing children.” In adulthood, the sisters decried the circumstances of what was actually a very unhappy childhood and in 1998 they wrote an open letter to the parents of the first surviving septuplets urging them to protect their children’s privacy.

8a

Eva Zeisel was one of the most notable industrial designers of the twentieth century. She designed Tomorrow’s Classic dinnerware for Hall China. It went into production in 1952, in Bridal White along with eight other patterns. Because of its beautiful design, low cost, and the wide variety of patterns available, it was an immediate success. Eva Zeisel believed in a playful search for beauty, and that is reflected in all her designs. Each piece is strong yet elegant, fluid yet playful. She once wrote that “beauty is not an elitist’s enjoyment. The sunset’s colors are for all to enjoy.”At the time she created this dinnerware as a freelance designer she was teaching at the Pratt Institute in New York. Tomorrow’s Classic became the number one selling dinnerware of the 1950s. There were a total of forty-one forms in this dinnerware line. She believed that pieces in a dinnerware set “should look like cousins — not brothers, that’s too close.” Affordable for newlyweds, each starter set included sixteen pieces (four each of dinnerplates, bread and butter plates, cups and saucers) and sold for around $9.95.

8b

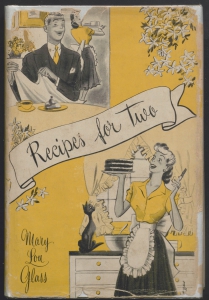

| Mary Lou Glass. Recipes for Two. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1949. The Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive. Gift of Janice Bluestein Longone. |

In the aftermath of World War II, there was much emphasis on the happy middle-class nuclear family, in which the husband came home from the office in a business suit to find his stylish but domestic wife ready to serve multi-course meals. Regardless of the great variation in how this vision played out (or didn’t) in real life, it was a powerful and pervasive ideal in mid-century American life.

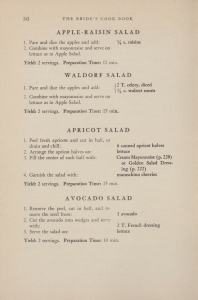

And before the nuclear family comes the nuclear couple. By this time it was far less common for middle-class American women to have hired help in their kitchens, although more and more owned labor-saving household machines, from washing machines to home freezers. On her own in the kitchen, a new bride could turn to Mary Lou Glass’ Recipes for Two to find recipes tailored for a standalone couple. Many recipes seem genuinely useful to a novice cook, like small-batch apple or chicken salad. A few however strain credulity, like the recipe to make precisely four cream puffs!

Apple-Raisin Salad

Pare and dice [two] apples and add: ¼ c. raisins

Combine with mayonnaise and serve on lettuce as in Apple Salad.

Yield: 2 servings. Preparation Time: 12 min.

9a

In the 1950s the standard poodle was the most popular breed of dog in the United States. The poodle became a beloved design element. Lucille Ball had a poodle haircut. There were the felt swing skirts — the fabric was cut in a full circle — with appliqued poodle designs that were first created by Juli Lynne Charlot, spaghetti ceramic poodles in pink and black and white, and poodle-themed costume jewelry. The motif was used on dishes, too.Glidden Pottery, founded by Glidden Parker, produced a unique stoneware dinnerware and Artware from 1940 to 1957. Glidden Parker had been a student of Marion Fosdick and well-known ceramic industrial designer Don Schreckengost at the New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University. Chi-Chi Poodle is the name given to one of the two poodle designs produced at Glidden Pottery. The story is told that the hand-painted designs of Chi-Chi, which first appeared in 1951, were based on the black standard poodle, Charlemagne, the dog owned by the family of Mr. Fenner, an Alfred banker who invested in Glidden Pottery. The shapes were created by Glidden Parker, while the decoration is attributed to June Chisolm, who received royalties on the design until it was discontinued in about 1955. The poodles decorate squared plates, tumblers, cups and saucers, shirred egg servers, salt and pepper shakers, and even ashtrays and cigarette boxes. Each piece was hand-painted, so no two are identical.Glidden Pottery was located in the small village of Alfred, New York, about a hundred miles from Jamestown, New York, where Lucille Ball grew up. She knew about the pottery and she and Desi Arnaz purchased a set of Glidden Pottery dishes in the Feather pattern for their own home. People who love I Love Lucy and Glidden Pottery enjoy watching the vintage programs to see Glidden Pottery in use on the coffee table and elsewhere. There is even an episode where Lucy can be seen stubbing out her cigarette in one of the Glidden Pottery shirred egg servers on the coffee table! A memorable advertisement for Simtex tablecloths featured this poodle-bedecked Glidden Pottery and could be seen in popular magazines between 1951 and 1955.

9b

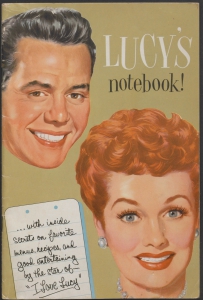

| Lucy’s Notebook!: With Inside Secrets on Favorite Menus, Recipes, and Good Entertaining by the Star of “I Love Lucy.” [New York?]: Philip Morris, [1950?]. The Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive. Gift of Janice Bluestein Longone. |

Actor and producer Lucille Ball is best remembered for her title role in I Love Lucy, a 1950s television sitcom featuring the misadventures of Lucy McGillicuddy Ricardo, a housewife who longs for fame, and her husband Ricky Ricardo, played by Lucille’s real-life husband Desi Arnaz, a Cuban-American bandleader, actor, and producer. Lucy was the first sitcom to be shot on three cameras and on film before a studio audience. In Sitcom: A History in 24 Episodes, Saul Austerlitz explains the significance: using three cameras instead of one allowed long shots and close-ups to be captured simultaneously. Previous sitcoms were typically broadcast live on one camera from the East Coast, filmed off a monitor as they aired, and distributed to the West Coast as a low-quality reproduction. Ball and Arnaz, however, leveraged their creative control over the show to record their performance on celluloid and edit the show together before distributing the same high-quality broadcast across the U.S.

Lucy’s Notebook! is written in the bubbly voice of Lucy Ricardo, offering advice on menus, parties, and “how to keep your husband kissing you twice a day.” Photos and “quotes” from Ricky carry the sitcom’s comedic repartee into the text, as when Lucy comments: “Me — I’m always hungry. Big breakfast, big dinner, big in-between snacks, big … well, a girl has to keep up her energy, doesn’t she?” as Ricky’s doubtful-looking floating head asks, “Energy? Sure! But did you ever marry a non-stop explosion …?”

Ham and Egg Nests

Grind the end of leftover baked ham very fine, season with a little dry mustard or Worcestershire sauce. Shape into firm nests on greased baking sheet. Drop an egg into each nest, then sprinkle with salt and pepper. Cover with aluminum foil. Bake in a moderate oven, 350˚F, for 10 to 15 minutes or until eggs are set.

10a

American designer Russel Wright (1904–1976), best known for his innovative designs for dinnerware, had a lifelong preoccupation with nature. His obsession with combining new materials and natural imagery can perhaps best be seen in his Melmac plastic Flair dinnerware line launched in 1959. His pattern Ming Lace Leaves featured tinted leaves of the jade orchid tree, imported from China and imbedded in the dishes, adding variety and individualization to these mass-produced wares. Each piece was unique. Other patterns in the series, but without the leaves, were titled Spring Garden, Arabesque, and Golden Bouquet.

10b

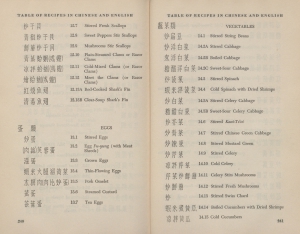

| Buwei Yang Chao. How to Cook and Eat in Chinese = Zhongguo Shi Pu = 中國食譜. New York: The John Day Company, 1945. The Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive. Gift of Janice Bluestein Longone. |

Buwei Yang Chao was born into a prestigious family in Nanjing, China. With the support of an open-minded grandfather, she rejected an arranged betrothal, trained at Tokyo Women’s Medical College, and practiced medicine in Beijing until her marriage to linguist Yuen Ren Chao in 1921 and subsequent immigration to the United States.Buwei Yang Chao’s cookbook is a technically masterful and linguistically witty collaboration with her husband, who took the lead in writing the English prose.

They coined several American terms for Chinese cooking that have become commonplace, like potstickers and stir-fry. In the latter case, the authors explain, “the term ch’ao . . . cannot be accurately translated into English. Roughly speaking, ch’ao may be defined as a big fire-shallow-fat-continual-stirring-quick-frying-of-cut-up-material with wet seasoning. So we shall call it a stir fry.”

Writing generally about twentieth-century Chinese cookbooks in America, Dr. Yong Chen points out that these texts “were not merely translating or introducing China’s cuisine to American audiences … rather, they represented an unprecedented effort to define and articulate Chinese food.” Dr. Charles W. Hayford argues that How to Cook and Eat in Chinese takes a step further by consciously situating the culinary arts within a post-World War I Wilsonian schema of “cultural internationalism,” in which scholarship and artistic endeavors would be shared amongst nations. Making Chinese food technically accessible, aesthetically appealing, and ultimately important to the everyday American cook was a mission that the authors saw as part of their larger commitment to “a Wilsonian agenda of equality and cosmopolitan world understanding.”

Celery Stirs Mushrooms

1 bunch celery

½ lb. fresh mushrooms

2 tbsp. vegetable oil

2 tbsp. soy sauce

1 tsp. salt

1 tsp. sugar

Wash the celery and cut into inch-long oblique cuts. Wash mushrooms and cut into ¼ inch-thick slices. Heat the vegetable oil in a skillet over a big fire until hot. Then put the mushroom slices in first and stir for 1 min. Then add in the soy sauce, salt, and sugar, and then add in the celery right after and cook together by constantly stirring for 3 min.

11a

American Modern earthenware dinnerware designed by Russel Wright was a best-seller for newlyweds in America from 1939 to 1959. Consumers were encouraged to mix and match the wonderful colored glazes with such attractive names as Coral, Granite, Chutney, Sea Foam, and Chartreuse. Wright designed the children’s plastic toy set for his daughter, Annie, in the mid-1950s. It was manufactured by the Ideal Toy Company and marketed through Sears. A large set for four or five cost around $4.95 in the 1950s. The child’s sets featured the same mixing of the colors that was marketed to adult users and included plastic stemware that looked like wine glasses and utensils, too. Their ad campaign was based on the slogan “Just Like Mommy’s,” because the toys were really just smaller plastic replicas of the adult dishes that were so popular. The child’s plastic version even had speckles in the plastic, to make them look more like the adult ceramic dishes, and colors that were intended to match the ceramic colors of Coral, Granite, and Chartreuse. Some have noted that these child’s plastic dishes were more popular than some of Wright’s adult plastic dish designs, such as the pattern Residential. They remain highly collectible today.

11b

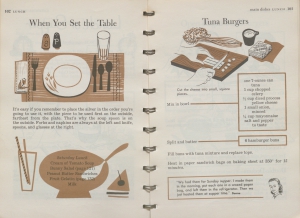

| Betty Crocker. Betty Crocker’s Cook Book for Boys and Girls. New York: Golden Press, 1957. The Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive. Gift of Catherine Mermelstein. |

This illustrated children’s cookbook provides a range of simple recipes, from S’mores over a campfire to Sloppy Joes for dinner, as well as an introduction to kitchen and table etiquette, such as the diagram on display demonstrating the proper way to set the table.Although Betty Crocker was a household name for much of the twentieth century, she was never a real person at all. The advertising department of Washburn Crosby Company (later General Mills) created the persona in 1921 as a single name under which staff could respond to requests for culinary and household advice. Subsequently, several different women played Betty Crocker on radio and television, and her official portrait has been updated multiple times to keep pace with changing aesthetics and gender expectations. The most famous Betty Crocker cookbook was Betty Crocker’s Picture Cookbook (1951), which brought simple recipe instructions and color illustrations together on each page. Betty Crocker’s Cook Book for Boys and Girls brought a similar approach to introducing children to the kitchen.

Sloppy Joes

You will need:

ground beef

catsup

tomato soup

hamburger buns

Brown the meat and crumble it with a fork. Stir in catsup and tomato soup. Heat it until it bubbles. Serve in buns.

12a

Aladdin Industries is best known for its line of character lunch boxes, including Superman, Mickey Mouse, and the Jetsons. The company began producing metal lunch boxes in the 1940s when they moved their headquarters to Nashville, Tennessee. Their first popular character lunch box featured Hopalong Cassady. This popular branding increased their sales from 50,000 units the first year to 600,000 units. This Pop Art domed tin lunchbox in the shape of a loaf of sliced bread dates to 1968. An identical example is located in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. This clever lunch box may bring to mind the expression, “the best thing since sliced bread.” While people have been baking bread for at least thirty thousand years, pre-sliced bread was first marketed on July 6, 1928, when the first automatically sliced commercial loaves became available.

12b

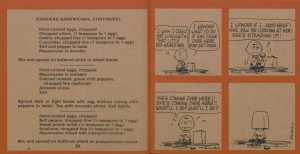

| June Dutton. Peanuts Lunch Bag Cook Book. [San Francisco: Determined Productions, 1970]. The Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive. Gift of Janice Bluestein Longone. |

Charles M. Schulz’s Peanuts comic strip ran from 1950 to 2000, drawing humor and commentary on the human condition from the interactions of elementary school boy Charlie Brown, his friends, and his dog Snoopy.

In the early twentieth century, most children went home at for their mid-day meal, but by the 1960s many ate lunch at school, whether as part of burgeoning school hot lunch programs (bolstered in the 1940s and after by the National School Lunch Act) or from lunch bags and lunch boxes brought from home. Lunch bags are often in the background of Peanuts comic strips, whether Charlie Brown is eating alone on a bench, bemoaning his inability to find the courage to talk to “that little red-haired girl,” or walking to school with his friend Linus. In the April 25, 1966, strip Linus offers a solution to his mother “always complaining about having to make lunches.” He explains to Charlie Brown that today he made his own lunch . . . “eight candy bars!”

As an alternative to Linus’s solution, June Dutton offers a host of recipes for sandwiches, salads, and desserts. A few recipes are named for characters, such as “Linus Loves Liverwurst Sandwiches,” and “Schroeder’s Harmonious Ham Sandwiches.” There are also two recipes for home-made bread, for those who may not be convinced that store-bought sliced bread is “the best thing since sliced bread!”

Egghead Sandwiches

Hard-cooked eggs, chopped

Mayonnaise to moisten

Canned roasted, green chili pepper, chopped fine (optional)

Avocado slices

SaltSpread dark or light bread with egg mixture (using chili peppers to taste). Top with avocado slices. Salt lightly.

Suggestions for Further Reading

- Austerlitz, Saul. Sitcom: A History in 24 Episodes from I Love Lucy to Community. Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2014.

- Carney, Margaret. Glidden Pottery. With essays by Ron Kransler and Wallace Higgins. Alfred, NY: Schein-Joseph International Museum of Ceramic Art, 2001.

- Chen, Yong. “Recreating the Chinese American Home through Cookbook Writing.” Social Research 81, no. 2 (2014): 489–500.

- Hayford, Charles W. “Open Recipes, Openly Arrived At: ‘How to Cook and Eat in Chinese’ (1945) and the Translation of Chinese Food / 食譜的開放與普及《中國菜的烹調與食用方法》及其翻譯問題.” Journal of Oriental Studies45, no. 1/2 (2012): 67–87.

- Kransler, Ronald J. Glidden Pottery: Alfred Mid-Century Highstyle Stoneware. Irvine, Calif.: Universal Publishers, 2011.

- Nicholas, Jane. “Quintessential Childhood: Showing Care in the Exhibition of the Dionnes.” Journal of Curatorial Studies 8, no. 1 (2019: 27-50).

- Pabst Brewing Company. The Great Pabst Brewery Milwaukee. Milwaukee, Wisc.: Pabst Brewing Company, 1907.

- Shapiro, Laura. Something from the Oven: Reinventing Dinner in 1950s America. New York: Viking, 2004.

- Taylor Philips, Danielle. “Moving with the Women: Tracing Racialization, Migration, and Domestic Workers in the Archive.” Signs 38, no. 2 (2013): 379-404.