Dining Grails

<! div style=”margin-top: -232px;”>

Dining Grails

Dining Grails, one of IMoDD’s two inaugural exhibitions in our first brick and mortar facility in Kingston, New York, is a subjective exhibition, really a perspective of where IMoDD is in its development, in 2024.

The collection started with approximately 1,200 objects in the permanent collection, and is now, a decade later more than 9,000 dining relating objects ranging from functional dinnerware masterpieces manufactured by international companies who engaged the leading designers for industry, as well as one of a kind works created by contemporary ceramicists, and artists using clay, glass, wood, metal, plastic, paper, fiber and more. IMoDD collects fine art (sculpture, paintings, photographs) related to the topic of dining. And a bit of kitsch, too.

What is a “holy grail” in terms of dinnerware? Is it a museum “wish list” realized? Knowing that the International Museum of Dinnerware Design must have an Eddie Dominguez masterpiece full service for twelve in the form of a Rose Garden from 1999. And then pursuing it when one magically appears on the market? Is a “dining grail” a masterpiece? A piece that stands the test of time or is, indeed, timeless? Is a dining grail a piece or pieces that “complete” a set at least in your own mind or in terms of your own collecting goals and value. Is it adding significant pieces to a dinnerware set. Is it the addition of the Russel Wright Theme Formal teapot or the addition of a rare lacquerware/bakelite covered bowl? Or is it having enough Theme Formal to set a table for a dozen guests?

Is a dining grail a beautifully designed single piece or set of dinnerware that makes food and beverages look appetizing? Is it playful and something one wishes to use every day to share with family or friends? Or does it “belong in a museum”? “Museum quality”?

I am still mesmerized by WASARA designed by Shinichiro Ogata in 2008. It is single use, tree free, biodegradable, sustainable, so beautifully designed that one doesn’t want to throw it away. Sushi looks good on it, as does lasagna. Masterpieces.

Wire scribble sculpture in the collection of IMoDD by Portuguese sculptor David Oliveira is a dining grail for the collection. It may be the most popular essence of dinnerware for visitors to the collection. It excites the imagination with its appearance like a drawing when photographed, but it’s three-dimensional genius. Light it properly and let the shadows and lines do their magic.

Not all dinnerware designers are household names unless you collect Russel Wright or Eva Zeisel’s designs and Mid-Century Modern is “your thing.” Most people recognize the name of Pop Art artist Roy Lichtenstein, even if it takes a minute to conjure up the comic book style images he is most famous for. His dinnerware designs for restaurant china manufacturer Jackson China sport those same recognizable black and white design motifs in his now iconic 1966 set made for the “Breakfast after the Happening.” This limited edition set (800) sold for $50 according to the advertisements in Art in America. The original paper ad from the journal cost in excess of $50 when purchased on eBay in 2015. The IMoDD breakfast set has been a Promised Gift of John and Susie Stephenson since 2012.

Each dinnerware collector has his or her “dining grails.” It is hoped that this exhibition is the catalyst for many conversations around the table with friends and family.

Eddie Dominguez

Eddie Dominguez (American, b. 1957)

73-piece Rose Garden sculptural dinnerware set with 12 place settings in the form of large green leaf plates, green stem cups, red rose saucers, red rose bowls, and red rose bud salt and pepper shakers, 1999

terra cotta (thrown, hand-built, carved, low-fired, underglazed, and glazed) with leather and copper rectangular base

2021.81 Museum Purchase

Ceramicist Eddie Dominguez was born in Tucumcari, New Mexico in 1957. He earned a BFA in Ceramics from the Cleveland Institute of Art in 1981. In 1983, he received his MFA from the New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University, Alfred, New York. He began teaching ceramics and sculpture at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln in 2000. Eddie won the New Mexico Governor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts in 2006 and a Distinguished Professor Grant from the New Mexico Highlands University, Las Vegas in 2008. By 2018 he had held over forty-five solo exhibitions and participated in more than 150 group exhibitions. His work can be seen in over thirty-five public collections throughout the United States, including the Smithsonian Institution’s Renwick Gallery in Washington, D.C. and the Museum of Fine Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

An online interview with questions by Margaret Carney and responses from Eddie Dominguez in September 2024, resulted in this dialogue:

Margaret Carney: How did you first discover ceramics, painting, etc. and find your place as an artist?

Eddie Dominguez: My first encounter with ceramics happened when I was a junior in high school and worked with a local potter. However, at this point, I was more interested in becoming a painter. It wasn’t until I attended the Cleveland to Art that I took a ceramics class and like so many fell in love.

MC: What are the greatest influences on your work? What motivates you? What guides your work.

ED: I would say as influences go that the landscape and my backyard garden are my strongest resources. I appreciate art history and the history of ceramics, however when it comes to personal influences, what’s right in front of me is what motivates me.

MC: What other creative outlets do you enjoy?

ED: I feel that I have many creative outlets. Teaching certainly motivates my creativity, growing a garden in cooking from it.

I grew up in an upholstery shop so enjoy restoring furniture and sewing.

I find working with community in a creative environment, very beneficial to my thinking.

I enjoy the sounds of nature, the wind the rain the birds singing.

MC: How did you come up with the idea for the rose garden installations of dinnerware?

ED: As a painter and drawer, I was considered an artist. When I majored in clay, I was considered a craftsman. I was interested in the differences in why they were viewed that way. It appeared to me that making pottery was at a lower level in the art world when compared to painting and sculpture. In my mind, I believed that if I used dinnerware forms and stacked them to become sculpture and utilize ideas about painting, that it might resolve the issue of Art versus Craft that was being discussed in the 70s.

MC: What questions do you ask yourself everyday?

ED:

Cultivate an Obsession.

“While most good students of natural history are observant of life around them generally, it is also beneficial to always be working with a specific question in mind — a particular group, species, or issue upon which you lavish thought, study, and attention… a good question fills us with a sense of purpose and gives structure to our observations. It engages our mind on levels unforeseen. It leads to more knowledge than hapless wandering about can, and rather than narrowing the creative response, it seems, somehow, to mysteriously expand it. Questions lead to further questions, and inquiry breeds insight. Gathering expertise brings both confidence and consolation.”

– ERIN SCHOENBECK

How can I live life optimistically?

What in life makes me the happiest?

What am I going to cook for dinner?

How can I best help my students?

What am I grateful for today?

I wonder what I can do to make my life better for me and others to live in.

Aladdin Industries Lunchbox

Aladdin Industries Incorporated (established in Chicago, 1908)

loaf of sliced bread domed tin lunchbox with a yellow collapsible plastic handle, ca. 1968

tin, plastic

2020.16 Museum Purchase

Aladdin Industries is best known for its line of character lunch boxes, including Superman, Mickey Mouse, and the Jetsons. The company began producing metal lunch boxes in the 1940s when they moved their headquarters to Nashville, Tennessee. Their first popular character lunch box featured Hopalong Cassidy.

This popular branding increased their sales from 50,000 units the first year to 600,000 units. This Pop Art domed tin lunchbox in the shape of a loaf of sliced bread dates to 1968. An identical example is located in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. This clever lunch box may bring to mind the expression, “the best thing since sliced bread.” While people have been baking bread for at least thirty thousand years, pre-sliced bread was first marketed on July 6, 1928, when the first automatically sliced commercial loaves became available.

essay by Margaret Carney

Robert Sabuda

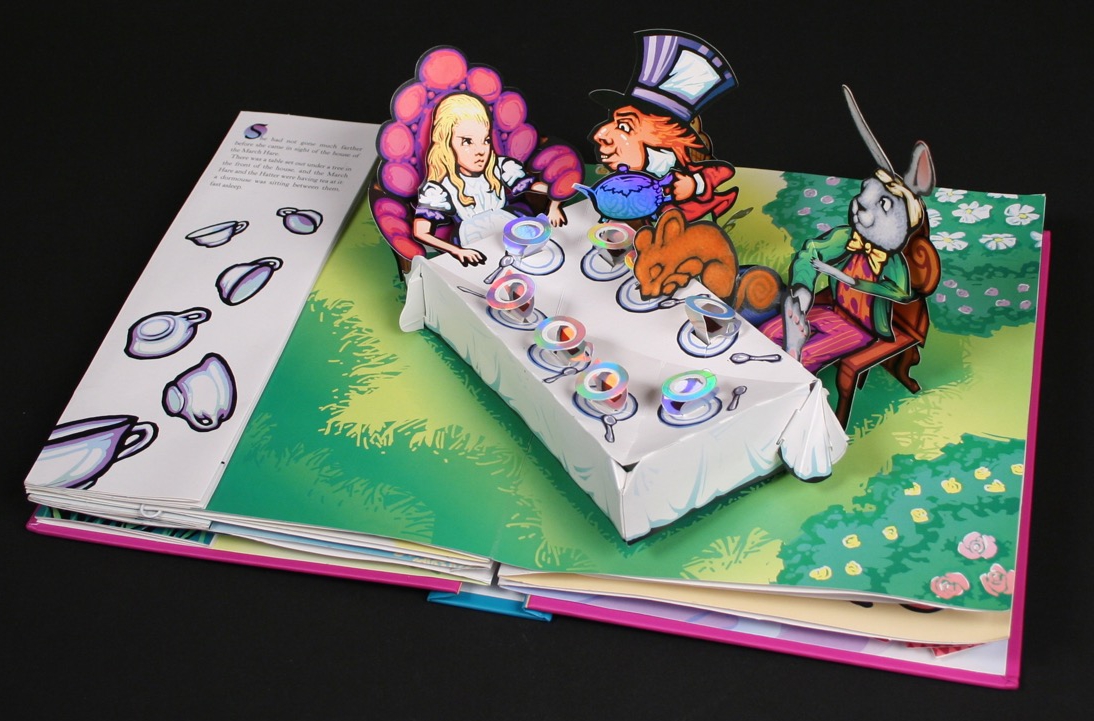

Robert Sabuda, illustrator (American, b. 1965) and Lewis Carroll

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland: A Pop-up Adaptation, 2003

novelty book, 12 pages

2014.177 Museum Purchase

An online interview with questions by Margaret Carney and responses from Robert Sabuda in October 2024, resulted in this dialogue:

Margaret Carney: How did you first discover your creative talents?

Robert Sabuda: I don’t ever recall a time when I was not drawing or making something! From the moment I could hold a crayon I think my destiny was set. Fortunately I had very supportive parents who encouraged me in this direction. When I got to high school I had an amazing art teacher who set me in my path to attend Pratt Institute in New York City, I developed a love of children’s book illustration there and have been VERY fortunate to now have this as a career.

MC: There aren’t so many gifted pop up book designers. What inspired you in this direction?

RS: I’d been illustrating children’s books, using 2-dimensional art, for about seven years. My techniques included paper collage, paper mosaic and paper batik. Clearly I loved working with paper, so I asked myself “how could I create illustrations using paper in 3-dimensions?” The answer was pop-up illustrations!

MC: What other creative outlets do you enjoy?

RS: This work takes up so much energy that I have very little time for anything else! Believe it or not, when I have down time from illustrating I don’t do any other creative work. But I’m a very active cyclist and practicing yogi.

MC: How do you choose the subject or focus of your pop up creations?

RS: Most people think that children’s book writers and illustrators create their work with a children’s audience in mind. But the reality is they are usually creating their work for the child in themselves. Everything I create is for the child in me. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland are my favorite stories, so it’s natural for me to choose these as subjects for a pop-up book. I LOVE winter and Christmas so many of my pop-up books reflect this as well.

David Oliveira

David Oliveira (Portuguese, b. Lisbon 1980)

20-piece 3D Wire Sketch Sculpture, 2012

wire

2012.15 Museum Purchase

David Oliveira (b. 1980) is a wire sculptor who lives and works in Lisbon, Portugal. He graduated in 2008 with a degree in sculpture with a specialty in ceramics from the University of Lisbon. He later took Master’s courses in drawing and comparative anatomy. He considers his sculptures to be drawings or 3D drawings. During a 2019 interview with Deborah Blakely for ZoneFineArts (https://zoneonearts.com.au/david-oliveira/) he said he was “searching for a way to draw in the air.” He found that wire offered the resistance and aesthetics he was looking for. He uses several kinds of lines ranging from galvanized wire to silver to iron. The gauge of the wire is based on the density of the line he wants to represent. He noted that “besides being sculptures they are also structures.” When he uses colored wire, he uses several types including a velvet coating which he feels is “warm, cozy and nice to the touch.”

The black coating on the wire used to create the wire scribble sculpture of dinnerware serves as a protection from corrosion, in addition to its aesthetic appeal. His wire sketches mimic rough drawings in 3 dimensions. According to at least one observer, they must be viewed at a particular angle or they dissolve into abstraction. He plays with optical illusion and encourages the viewer to fill in gaps with their imagination.

His subject matter varies from the dinnerware one sees here to anatomical studies, animals and birds, botanicals such as Bougainvilla (with color), and the Pieta. His works are normally created on a natural scale, true to life, but he occasionally creates on the small scale, fragile grasshoppers, bees, snails, dragonflies and spiders.

He has exhibited internationally and won numerous awards and honors. The International Museum of Dinnerware Design first learned about this exceptional artist and his work from a Facebook posting in 2012 by Garth Clark. IMoDD’s curator Margaret Carney, messaged the artist, they agreed on a price. She likes to tell people that she (rather appropriately) “wired” Euros to the artist to complete the acquisition. It is a favorite among all visitors and has been previously exhibited in Chicago at Navy Pier during SOFA Chicago (Sculpture Objects Functional Art+Design) and Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Essay by Margaret Carney

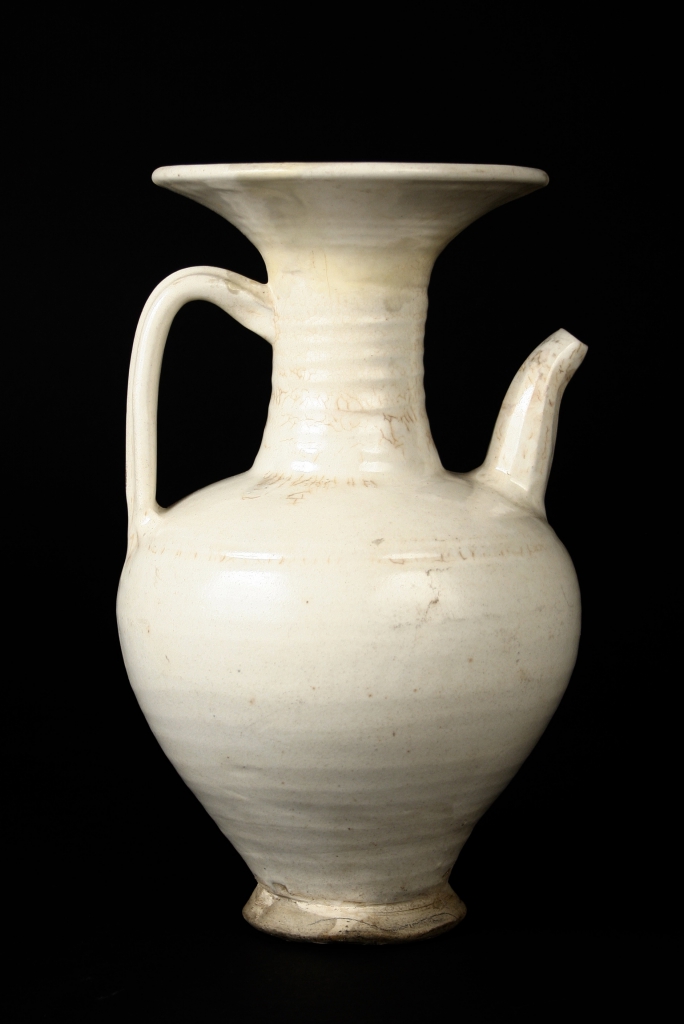

Chinese Song dynasty Cizhou ware ewer

Song Dynasty, China (960-1279)

Chinese Cizhou ware ewer with Chinese “Dong” family name on base,

originally excavated from Julu Xian, Hebei Province, ca. 1108 A.D.

porcelaneous stoneware, white slip, clear glaze

2020.100 Museum Purchase

One might be surprised that there is more than one piece of dinnerware from China’s Song dynasty (960-1279) in the collection of the International Museum of Dinnerware Design. Actually there are a little more than a half dozen pieces of table ware from one specific village in China, and this ewer is the most outstanding example.

There is a remarkable story that surrounds this beautiful object that might remind one a bit about the artifacts recovered from the buried city of Pompeii after Mount Vesuvius erupted in in 79 A.D. burying everyone and everything in volcanic ash. Although a tragic event in human history, the excavated Pompeii provides a rich story of Roman daily life at the time of the eruption. A similar scenario unfolded in Julu and neighboring areas, in what is now present day southern Hebei Province in 1108 A.D. when it was inundated by a flood of the Yellow River when it burst its banks. Northern Song Julu, including its ceramics, remained preserved, intact, buried in the silt of the Yellow River for nearly 800 years. Cizhou ware ceramics from this site have a rust colored stain in the crazing of the glaze due to iron in the silt in which they were buried for 800 years.

The Roman city of Pompeii was never completely forgotten, and discoveries were made on a regular basis. After 1860, the whole city was excavated block by block. The ancient city of Julu was not forgotten. Oral histories passed down from family to family survive. In 1918, farmers digging wells during a drought discovered the buried Song Dynasty city of Julu and its artifacts. Objects were sold to antique dealers in Beijing and many pieces were sold to museums and collections abroad. And that is likely how this fine piece, which has extensive restoration around the trumpet shaped top, eventually came to be owned by this person and that person until it finally went up for auction in 2020 in Switzerland, and was acquired by IMoDD.

There have always been comparisons between Pompeii and Julu the moment artifacts from this ancient Song dynasty marketplace were recovered. Sometimes it was even referred to as “China’s Pompeii.” The story is more complicated and too long to include here. However, in addition to their intrinsic beauty, ceramics recovered from this datable site, some with inscriptions with actual dates, all created before the 1108 A.D. time of inundation, offer a rare collection of artifacts from one Northern Song dynasty type site.

When examined carefully individually and as a whole, these ceramics offer a window into the material culture of the Northern Song and their shared attitudes towards food and dining. This group of datable ceramics emphasizes the dominance of Cizhou wares in the early 12th century and when the other ware types are included, it provides a useful indication of the variety of ceramics in use by households in the area.

This area that is the archaeological ancient Song dynasty Julu is now a protected area and new excavations have begun. The goal of this curator is to see that Julu receives the world’s attention and recognition that Pompeii has received. Everyone has heard of Pompeii. Few have heard mention of Julu. Pompeii is a World Heritage site. The ancient Song dynasty Julu deserves the same protection. Stay tuned.

essay by Margaret Carney

Léopold Foulem

Léopold Foulem (Canadian, b. New Brunswick 1945-2023)

Imari-Style Teapot, 2000-2001

ceramic and found objects

2024.5 Anonymous Gift in Memory of Léopold Foulem

Léopold Foulem (1945 – 2023) was one of the leading conceptual ceramic artists in the world. He was known for his distinct marriage of Baroque and pop art styles, and employed ready-mades, abstraction and assemblage in his work. His work was often irreverent and provocative, deconstructing issues of gender, taste and the paradox between the three-dimensional object and the two-dimensional image. His work challenges the viewer to consider ceramics as an artistic discipline unto itself rather than a process, material or utilitarian object.

Foulem was born in Caraquet, New Brunswick. He taught ceramics in Montreal at the Collège d’Enseignement Général et Professionnel (CÉGEP), while maintaining a studio and summer home in Caraquet. He lectured extensively on the topic of ceramics as an autonomous art form, and was a leading scholar on Picasso’s ceramics. His work is in the collections of numerous museums and he has been recognized with numerous awards, including the Order of Canada – the highest civilian distinction available in the country.

Imari-Style Teapot featured in this exhibition is a non-functional teapot that references a historical style through its shape and decoration. The body and spout of the teapot are solid and are mounted on a ready-made metal stand that incorporates the handle. This is part of a body of his work that referenced historical ceramics in a non-functional manner, thus challenging our presumed stereotypes about ceramics.

References: https://cfileonline.org/newsfile-remembering-warren-mackenzie-leopold-foulem-more/; https://studiopotter.org/news/remembrance—léopold-l-foulem

essay by Bill Walker

William Parry

William Parry (American, 1918-2004)

KFS (Knife Fork Spoon) 28: Stand, 1994

white stoneware with black copper oxide slip

2012.3 Gift of Amanda Parry Oglesbee and Brian Oglesbee

Viewing William (Bill) D. Parry’s KFS (Knife, Fork, Spoon) 28: Stand from the permanent collection of the International Museum of Dinnerware Design, part of the inaugural exhibition Dining Grails, may be an unexpected experience for visitors expecting IMoDD to be collectors of exclusively and literally functional dinnerware such as traditional ceramic plates, glassware, and ubiquitous knives, forks, and spoons from everyday dining. Instead, the visitor is treated to an abstract representation, on a monumental scale, rather than the small personal items one utilizes while dining. A curator at the Philadelphia Museum of Art once described Parry’s approach to the KFS as “altering their otherwise common appearance and imbuing them with a sense of wonder.”

Bill Parry was born in 1918 in Lehighton, Pennsylvania. He served in the military from 1942-1945. It’s interesting that he first attended Alfred University in Alfred, New York as a ceramic engineering major, but switched to studio arts later. He received his BFA from Alfred 1947. He was a ceramicist and teacher for over forty years, teaching first at the Philadelphia College of Art (now University of the Arts), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania from 1948 to 1963. In 1963 he was appointed as a faculty member in ceramics at Alfred, where he taught until his retirement in 1989. There he taught alongside ceramic artists Val Cushing, Daniel Rhodes, Robert Turner, and Ted Randall.

Bill Parry may be best known for his ongoing experimental work, including his “Off Butterfly” (OB) and “Knife Fork Spoon” (KFS) series. He was continually exploring new methods and ideas. In the case of the KFS, each set of stoneware “implements” has stains and glazes applied in one solid coat. There is an archaizing effect, reminding one of ancient relics and excavated treasures. The result is dozens of unique KFS forms, no two identical. According to his catalogue raisonne his KFS series was begun in 1979-80 and continued into the 1990s. Another KFS set was recently donated to IMoDD, collected by the late Arthur J. Williams. Illustrated here, KFS 14, stoneware with copper oxide, dates from 1991-92. The set on view, KFS 28: Stand, dates from 1994, and was donated to IMoDD in 2012 by Bill Parry’s daughter and son-in-law, Brian and Mandy Parry Oglesbee.

essay by Margaret Carney

William Parry (American, 1918-2004)

KFS (Knife Fork Spoon) 14, 1991-92

stoneware with copper oxides

2024.60 Gift of Richard W. Gold from the Arthur J. Williams Collection

Glidden Pottery

Glidden Pottery, Alfred, New York (1940-1957)

Glidden Parker, designer (American, 1913-1980)

Sculptured Stoneware covered winged soups and triangular sandwich snack sets in Viridian, 1953

plate L: 9.75” x 7.25” cup W: 5.75” x 4” H: 2.75”

stoneware, glazed

Glidden Pottery nos. 541, 542

IMoDD 2014.26 Museum Purchase, IMoDD 2017.40 Gift of John Dolan, Mary Beth Sootheran, The Andover House

There are the well-known 20th century American designers for industry such as Russel Wright, Don Schreckengost, Viktor Schreckengost, and Eva Zeisel. And then there are an enlightened few that have discovered Glidden Pottery. Glidden Pottery is a unique stoneware bodied dinnerware and Artware that was produced in Alfred, New York from 1940-1957. Glidden Pottery utilized modern production methods of slipcasting and ram pressing, but each of the more than 300 shapes was individually glazed and hand-decorated.

The founder of Glidden Pottery was Glidden Parker who had studied between 1937-39, as a special graduate student with Miss Marion Fosdick, one of the ceramics teachers at the New York State College of Ceramics in Alfred, New York. Noted ceramic industrial designer, Don Schreckengost was another of his well-known professors at Alfred.

Luncheon snack sets, some times referred to as bridge sets, were popular at ladies luncheons and bridge clubs in the United States and elsewhere during the 1930s-70s. They were primarily made of ceramic, glass, or plastic. Each set had a small tray or dish with a clearly designed space for a cup or small bowl to rest on the tray. English and Japanese versions exist, too. Some Japanese versions even had lithophanes with geisha heads featured in the bottom of the cups. As the ladies sat in livingrooms or casual locations, the small trays rested comfortably in their laps – where they could sip a beverage, have a tasty sandwich and possibly chat and smoke with their friends.

This luncheon snack set was part of the sculptured stoneware ensemble created circa 1953, utilizing Glidden Pottery’s popular viridian glaze. Winged punch bowls with matching cups with this same glaze were also created at this same time. It is one Mid-Century example of the convergence of good design and playfulness.

essay by Margaret Carney

Carl Auböck

Amboss, Vienna, Austria

Carl Auböck, designer (Austrian, 1900-57)

Maestro by Amboss stainless flatware service set, 1955

stainless steel

2017.37 Museum Purchase

Carl Auböck II (Vienna, Austria, 1900-1957) was an Austrian painter and designer, and a member of the Auböck family who for four generations have owned and managed the Vienna-based Werkstätte Carl Aubôck. The workshop was part of the Wiener Werkstätte which is known for its Modernist designs. It has been in operation for more than 120 years. He studied at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts and subsequently became one the first students at the Bauhaus. Following his studies he joined the workshop of his father in 1925. His prolific designs show the influence of Bauhaus modernism. His novel approach to designing domestic objects made him somewhat of a cult figure during his lifetime.

Auböck’s iconic design work from the 1940s has been described as “combining functionality with an excellent ability for detail and very importantly humor, (which) made him famous on an international level.”

Auböck won a gold medal at the 1958 World Exposition in Brussels for his beautifully designed Maestro stainless steel flatware set constructed from 18/8 stainless steel, pattern 2060 by Amboss Rostfrei of Austria which was designed in 1955. He is also known for his watercolor paintings. This should be no surprise as his early academic training was in painting. His design sketches were often painted rather than drawn.

References: https://www.casatigallery.com/designers/carl-aubock/

https://adeenidesigngroup.com/collections/carl-aubock

https://www.aubock.com/carl-auböck-ii

essay by Margaret Carney

A.D. Copier

Leerdam, Netherlands (est. 1878- currently part of Libbey)

A.D. Copier, designer (Dutch, 1901-1991)

Rondo liqueur decanter with 5 glasses, 1935

glass

2018.44 Museum Purchase

Andreis Dirk Copier (1901 – 1991) is possibly the best-known Dutch designer of glassware and decorative glass of the twentieth century. He spent almost 50 years as artistic director at the Leerdam Glassworks from the 1920s until his retirement in 1971. The son of a glass blower at the Leerdam factory, he began working for Leerdam as an apprentice at the age of 13 and at 17 was selected by the company to study typography in Utrecht, and later studied at the Rotterdam Arts Academy under sponsorship by the factory. He worked in advertising and publications and additionally began producing one-of-a-kind pieces in the glass shop. His first design went into production in 1923. He worked closely with craftsmen in the factory and succeeded in creating straightforward designs with technical perfection that were attractive and functional. Over the course of his career, he created over 10,000 designs for utilitarian and decorative glass. In addition, as artistic director, his responsibility included overseeing the work of other designers who produced a similar volume of work to his own.

The Rondo liqueur set was designed in 1935. With a simple style and no decoration it led to a stylistic change in Leerdam’s crystal products. The stopper on the decanter is a solid sphere and the base is heavy, making it solid and functional. Rondo was produced using subtle colors for a chic modern appearance, with an Art Deco flair. The small liqueur glasses beg you to hold them.

References: Joan Temminck and Laurens Geurtz, The Complete Copier, NAi Publishers, Rotterdam, 2012.

www.hogelandshoeve.be

Essay by Bill Walker

Roy Lichtenstein

Jackson China Company, Durable Dish Company, Falls Creek, Pennsylvania (1917-1985)

Roy Lichtenstein, designer (American, 1923-1997)

Place Setting, 1966

whiteware with stencil decoration, glazed

Promised Gift of Susanne and John Stephenson

There are not many designers of dinnerware that can be described as American Pop Artists. In fact, Roy Lichtenstein (American, 1923-1997) is the only one that immediately comes to mind. The Pop Art movement in the United States and United Kingdom emerged in the mid to late 1950s when artists such as Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Jasper Johns, and Claes Oldenburg challenged the traditions of fine art by including imagery from popular culture in their creations. This imagery included commonplace mass-produced cultural objects from everyday life such as comic books and advertisements. Lichtenstein’s precise artworks were often inspired by comic strips while parodying popular culture at the same time. His work is instantly recognizable by his use of commercial imagery as well as his use on a large scale of the Ben-Day dots associated with newspapers and comic strips.

Roy Lichtenstein and ceramicist Ka Kwong Hui (1922-2003) met when they were both teaching at Douglass College at Rutgers University circa 1960-63. Their collaborations occurred in 1964 and 1965. Technical assistance was provided by Hui in 1965, when Roy created his ceramic mannequin head sculptures, and also when Lichtenstein created his crockery sculptures in 1965-66. Hui created the molds for these pieces and additionally developed the glazes and overglazes. When they were exhibited at Leo Castelli Gallery in New York in 1965, Jeff Schlanger described the year-long collaboration between Lichtenstein and Hui as “crockery castings from a series of cafeteria style commercial molds reassembled in precarious stacked and tipped positions and fired at cone 06 and sprayed overall with a white majolica glaze.” They have further been described as being made with “as much skill as wit.” (Slivka)

At the same time as these collaborations with Ka Kwong Hui, Roy Lichtenstein designed this limited edition black and white 6-piece place setting for Jackson China. The advertisement that appeared in Art in America the same year noted the set was “For breakfast after the Happening. Dishes by Roy Lichtenstein.” “Here’s a limited edition of china dinnerware, designed inside and out in black and white by Roy Lichtenstein. There are only 800 of these signed place settings. Each is individually boxed as a six-piece place setting, and includes one dinner plate, one salad plate, one bread and butter plate, one soup bowl, one cup and saucer, plus a numbered certificate. The dishes cost a great deal. $50 per place setting. Available at the Leo Castelli Gallery, 4 East 77th Street, New York City. Add $2.50 freight charges east of the Mississippi per place setting, and $3.50 west of the Mississippi.”

References: Ceramics Monthly, “Hui: beautiful garments worn on top of the piece,” by Margaret Carney, Vol. 53, No. 5, 2005, pp. 41-45; Craft Horizons, “Ceramics and Pop –Roy Lichtenstein,” by Jeff Schlanger, Vol. 26, January-February 1966, pp. 42-43; The East Hampton Star, “From The Studio,” by Rose C.S. Slivka, August 27, 1992, p. H-11.

essay by Margaret Carney

Roy Lichtenstein (American, 1923-1997)

paper plate, 1969

screenprint in yellow, red, and blue on white paper plate

Diam: 10.25”

publisher: Bert Stern for On 1st, New York

printer: unknown, possible Artmongers Manufactory, New York

2025.1 Museum Purchase

In 1969, Pop Artist Roy Lichtenstein was commissioned by photographer and filmmaker Bert Stern to design a paper plate to be sold in Stern’s New York City shop for artistic objects called On 1st. It is believed that the paper plates were produced by Artmongers Manufactory in New York. They were sold in packages of ten wrapped in clear cellophane and it has been reported that a package sold for $1.00.

On 1st was located at 1159 First Avenue at 63rd Street in New York City and was based on Stern’s vision of a shop that was part fashion boutique and part art gallery with a focus on selling “practical objects” designed by artists at an affordable price. The façade was one-story-high sculptural letters “On” with “1st” painted on the wall beside it. The entryway to the store was through the “n”, the space in the “O” was filled with nine TV screens showing what was going on inside, and the interior was entirely covered floor to ceiling with royal blue carpet. Despite an investment of $150,000 to design and renovate the space, the shop was only open for a year or less after opening around December 1968.

The paper plates were marked on the back “Roy Lichtenstein © On 1st Inc. 1969.” It is not known how many were sold as the shop was only open for such a short time. In 1977 about 500 of the remaining paper plates were given by the artist to the art museum at University of California at Long Beach at the time of an exhibition of his work. These have the additional marking “Distributed / In Conjunction with the Exhibition / Roy Lichtenstein Ceramic Sculpture / February 21–March 20, 1977 / California State University/Long Beach.”

Arne Jacobsen

Stelton, Denmark (established 1960)

Arne Jacobsen, designer (Danish, 1902-1971)

Danish Cylinda line coffee and tea set, ca. late 1960s-1970s

Lauffer stainless steel, plastic

2014.160 Gift of Nancy and Tom Durnford

2022.110 Museum Purchase

Arne Jacobsen (1902 – 1971) was a Danish architect and designer whose work had a significant impact on both Danish and international design. While trained as an architect at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts and having a successful career in architecture spanning six decades, Jacobsen also made significant contributions to the world of design that rival his accomplishments in architecture.

Early in his career, Jacobsen’s work followed a neoclassical aesthetic which dominated the Academy at the time, but travel to Germany and exposure to the Bauhaus resulted in his transition to Modernism. His architectural projects often included the design of the interior furnishings and the surrounding landscape in addition to the buildings themselves.

In the years following the Second World War, Jacobsen pioneered the use of stainless steel as a functional and affordable alternative to traditional silver, first for cutlery and later for hollow-ware. His approach to design was to strip away elements he considered to be superfluous, resulting in designs that continue to be radical and forward thinking to this day. The Cylinda line, developed in partnership with the manufacturer Stelton, follows this design philosophy with its basic geometric shapes and aesthetic of industrial precision. The line was originally intended to be produced from standardized stainless steel tubes to reduce costs, however this approach was ultimately abandoned. When introduced in 1967, the Cylinda line was immediately recognized as an iconic design, receiving the Danish Design Council’s ID Prize and other awards.

References: http://arnejacobsen.com, Wikipedia article – Arne Jacobsen.

essay by Bill Walker

Eva Zeisel Museum white

Castleton China Company, New Castle, Pennsylvania (1940-1974)

Shenango Pottery Company, New Castle, Pennsylvania (1901-2009)

Eva Zeisel, designer (American, b. Hungary 1906-2011)

Museum white dinnerware, designed 1942-45, manufactured 1949-74

coffee pot, teapot, creamers, sugar, plates, bowls, cup & saucer, after dinner coffee cup and saucer, and prototype bowl

porcelain, glazed

2016.218-2016.225, 2017.185 Museum Purchases, 2017.61 Gift of Cheryl Blackwell, 2022.131 Gifts of Jean Richards, salt cellar and spoon on loan from Matthew Whalen and Frederick Sanders

In 1942, the newly formed Castleton China Company wanted to produce the first modern china dinnerware in the United States. Louis Hellman, a co-founder of Castleton China and the US representative for the German company Rosenthal Porzellan AG, became interested in modern design after he attended New York’s Museum of Modern Art 1941 exhibition Organic Design in Home Furnishings. Hellman asked the exhibit’s curator, Elliot Noyes, to recommend a dinnerware designer worthy of creating modern dinnerware shapes worthy of its own MoMA exhibition. Noyes recommended industrial designer Eva Zeisel.

In 1942, the newly formed Castleton China Company wanted to produce the first modern china dinnerware in the United States. Louis Hellman, a co-founder of Castleton China and the US representative for the German company Rosenthal Porzellan AG, became interested in modern design after he attended New York’s Museum of Modern Art 1941 exhibition Organic Design in Home Furnishings. Hellman asked the exhibit’s curator, Elliot Noyes, to recommend a dinnerware designer worthy of creating modern dinnerware shapes worthy of its own MoMA exhibition. Noyes recommended industrial designer Eva Zeisel.

In January 1942, Noyes had attended a lecture Handicraft and Mass Production by Eva Zeisel at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, where she described her vision of craftwork as an influence on industrial design. Because of her progressively modern design philosophy and her experience working in the pottery industry, Eva was awarded the Castleton project. Eva credited this commission with establishing her reputation in the United States remarking that “it made me an accepted first-rate designer rather than a run-of-the-mill designer.”

To begin development of the dinnerware line, Eva consulted the writings of Emily Post, the leading authority on manners and etiquette in the United States, to better understand the America idea of elegance at a formal dinner table. MUSEUM was designed to be sufficiently modern to meet MoMA’s high standards and to win the approval of customers with enough means to be able to purchase what was going to be very expensive dinnerware.

With a “family” of 25 shapes based on rounded squares, squared ovals and circles, Eva avoided what she regarded as the “monotony of many modern shapes.” MUSEUM’s fluid, ethereal shapes were designed so that they seemed to be “growing up from the table.” Heavy bottoms added stability, but, taking advantage of the delicacy of porcelain, transitioned to thin edges that had a wonderful transparency. Castleton said that “The forms of MUSEUM dinner service have the quality of superb sculpture and at the same time are functional and durable. They emphasize the inherent beauty of Castleton’s lustrous pearl-tone, its rare translucence. The ware itself, free of decoration, delights the eye and thrills of touch.”

With an eye toward modern dining, many of the pieces Eva designed for the line had not been seen before in formal dinnerware. Castleton noted that “Because MUSEUM is geared to contemporary living, a true product of the times, it includes many useful pieces not found in services of traditional design—the large square salad bowl, the handleless creamer, the open sugar bowl.” During MUSEUM’s development, Eva recalls MoMA’s curators controlling the design of each piece to within “every sixteenth of an inch” and at the same time they were tested for ease of production by Castleton. Dozens of alterations were made to make sure that the resulting design achieved “the effect of balanced movement with quietness” that was sought by Castleton, MoMA, and Eva.

Development was completed in 1943, but because of the war, MUSEUM was not shown until the MoMA’s 1946 exhibition New Shapes in Modern China Designed by Eva Zeisel. It was the first one-woman exhibition at MoMA.

During the exhibition, the china was available by special order through select department stores. Delivery time was promised in four months, but it took three years before MUSEUM went into full production in 1949. Although Eva had patented many of the designs, the contractual rights reverted to Castleton in 1948, leaving them free to do with the dinnerware line as they pleased.

Not all of the 25 pieces designed for the line made it into production. Salt cellars, small spoons, a candleholder/vase and a bouillon bowl were never mass produced. A downward handle that Eva had originally designed for the coffee cup was changed to an upright design without her consultation. To increase sales potential, decorated variations were added when none had originally been intended. They were promoted by their pattern name and for using the “MUSEUM shape.”

MUSEUM was difficult to produce and had to be fired at extremely precise temperatures. Delicate spouts and handle attachments required individual degrees of pressure to control the amount of shrinkage. The slightest error could crack and ruin the pottery. It was said that one of every five pieces were lost during the firing and assembly process. The labor intensive design and high failure rate meant that MUSEUM was very expensive. A service for twelve retailed for $300 ($3280 in 2020 figures).

This heirloom quality china dinnerware was “hailed both in America and Europe as marking a new epoch in ceramic history.” In its April 1959 issue, Fortune magazine in collaboration with the Institute of Design, and their director Jay Doblin, published a list of the “The 100 Best Designed Products.” Eva’s MUSEUM dinnerware for Castleton made 53 on the list. MUSEUM production continued for almost forty years until the late seventies.

Eva Zeisel was one of few women to pursue an industrial design career in the early twentieth century. Her exceptional designs would make her one of the most celebrated industrial designers of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

Born Eva Striker in 1906, in Budapest, Hungary, as a youngster, she had shown an artistic ability and curiosity. Her education and surroundings gave her a strong interest in the history and the current state of art, architecture, design and culture. She studied painting and seemed destined for a career as a fine artist. Although she was creative, and a dreamer, she was also pragmatic. In 1924, she became a pottery apprentice, deciding to learn pottery because that trade skill would provide her with means to support herself financially as a fine artist. At the time, it was not considered socially acceptable for women to apprentice as potters or artisans. In 1925, Eva set up her own pottery studio in the former gardener’s shed in the garden of her family’s home where she produced “black pottery” a well-known type of Hungarian folk pottery.

In 1926, she began working as a freelance designer for Kispester-Granit of Budapest. In preparation, Eva became acquainted with what she referred to as the “first mass-production pottery factory in Hungary.” Eva’s work at Kispester was whimsical, and had a flair of disorganized spontaneity, that she worked out through sketching, paper cut-outs and hand-modeling…a technique that she would use throughout her design career. During this time, she continued to indulge in her interest of art and cultural modernism, tempered with her respect for history and traditional Hungarian folk art.

Eva moved to Schramberg, Germany in 1928 to accept a job as the sole designer for Schramberger Majolikafabrik, which specialized in the manufacturer of household items such as dinnerware, vases and lamps. Not having the necessary drafting skills that the job required, she begged a qualified friend to teach her those skills during a day of intensive training. When asked by Schramberger whether she wanted to create new forms on a potter’s wheel or by drafting, she chose design by drafting to show that she was a real industrial designer, not a craftsman. Although Eva had designed for mass-production at Kispester, it was at Schramberger that she first consciously considered herself to be a designer for industry, a rare distinction for a woman of that era. Feeling that her Schramberg designs deserved recognition, Eva had requested that her signature be used in their pottery marking. Schramberg refused and in early 1930, Eva left the company to look elsewhere for new work and opportunities.

After several jobs in the Russian ceramics industry—Eva was named artistic director of the Russian China and Glass Trust. In May 1936, while living in Moscow, she was arrested and was falsely accused of participating in an assassination plot against Joseph Stalin. She was held in prison for 16 months, 12 of which were spent in solitary confinement. In September 1937, she was released and deported to Vienna, Austria. Some of her prison experiences form the basis for Darkness at Noon, the anti-Stalinist novel written by her childhood friend Arthur Koestler. It was while in Vienna that she connected with her future husband Hans Zeisel, later a legal scholar, statistician, and professor at The University of Chicago. A few months after her arrival in Austria the Nazis invaded, and Eva took the last train out. She and Hans met up in England where they married and sailed for the US with $67 between them.

In the United States, Eva had to reestablish her reputation as an designer. Beginning in 1937, she started teaching industrial ceramic design at Pratt Institute in New York and developed a working relationship with the Bay Ridge Specialty Company in New Jersey—where she designed pottery and her Pratt students could get real world experience in the pottery industry. Working with student Francis Blod, together they designed Stratoware for Sears, the first line of dinnerware that used Eva Zeisel’s name in its promotion.

Along with her 1942 MoMA and Castleton China Company MUSEUM dinnerware design commission, Eva would receive many more dinnerware design commissions and continue to work on other important industrial design projects throughout the 1950s and until her initial retirement in 1964. She was one of the few industrial designers who was able to effectively use her name in the promotion of her designs.

Zeisel stopped designing during the sixties and seventies to work on American history writing projects and a memoir of her time spent in a Soviet prison. In 1984, after a highly successful retrospective museum exhibition of her work Eva Zeisel: Designer for Industry, Eva returned to design. Among those designs were glassware, ceramics, furniture and lamps for the Orange Chicken; porcelain, crystal and graphic prints for KleinReid; glassware and giftware for Nambé; a tea kettle for Chantal; Classic-Century dinnerware made by Royal Stafford, combining pieces from her Hallcraft Tomorrow’s Classic and Century, with many pieces made from the original molds; a cutlery set for Crate&Barrel; and the Granit stoneware dinnerware set for Design Within Reach. Many of her later designs found the same success as her earlier designs.

Eva continued designing until her death in 2011 at the age of 105. Truly one of the most important industrial designers of the 20th century, Eva Zeisel’s work is in the permanent collections of museums throughout the world, and many of her useful designs are still in production.

Castleton China, Inc. began making fine porcelain in 1901 when New Castle China was created after purchasing the New Castle Shovel Works factory in New Castle, Pennsylvania. Soon after, the company acquired Shenango Pottery, a company that produced hotel wares and semi-porcelain dinnerware. In 1909, under the leadership of James MacMath Smith, they reorganized as Shenango Pottery Company.

In 1936, driven by fear of France being invaded by Hitler and the Nazi forces and to eliminate high American import duties, Haviland China of Limoges, France asked Shenango Pottery to produce Haviland products. From 1936 to 1958, Shenango produced Haviland porcelain with the stamp “Haviland—Made in America.” Rosenthal China of Germany struck a similar deal with Shenango, but these products were marketed under the Castleton China name.

In 1951, Shenango purchased all of the U.S. holdings of the Rosenthal Company, continuing to produce tableware products under the Castleton name. Castleton famously produced several dinnerware sets for the White House, including a commemorative plate for Dwight D. Eisenhower. After being purchased and re-sold several times through the last half of the 20th century, all Shenango Pottery Company production stopped in 1991.

References: Eva Zeisel: Life, Design and Beauty, Pat Kirkham, Pat Moore, Prico Wolfframm (Chronicle Books, 2013); Castleton China Museum, Promotional Brochure (Castleton China, Inc., New York, January 3, 1949); Castleton History (Replacements, Ltd., www.replacements.com).

essay by Scott A. Vermillion

Beth Lo

Beth Lo (American, b. 1949)

Take Out (Made in USA, Made in China), 2021

porcelain, hand-painted

2021.5 Museum Purchase

An online interview with questions by Margaret Carney and responses from Beth Lo in September 2024, resulted in this dialogue:

Margaret Carney: How did you first discover ceramics and your place as a contemporary artist?

Beth Lo: I was always drawing and making things as a child, but as a daughter of immigrant parents I was expected to go into the sciences. I discovered clay at a community center after my first year of college and I was hooked. I took a BGS degree which allowed me to take a wide variety of General Studies courses including art. (Fortunately as the second child I got a little more leeway than my older sister Ginnie who is a computer science professor. ) I continued with an MFA under Rudy Autio and succeeded him as University of Montana Professor of Ceramics in 1985. I have made a variety of work throughout my career, but my signature breakthrough came when I gave birth to my son Tai and began investigating images of family and my Asian heritage.

MC: What other creative outlets do you enjoy?

BL: I am a bass player and back up singer in a number of musical ensembles. I think I am lucky that Montana is such a low population state so that I was able to experiment musically without a lot of competition. I play both upright and electric bass in jazz combos, a Salsa group, a Brazilian ensemble, a Western swing group and have been a member of the swing, jazz band the Big Sky Mudflaps for 50 years !!!!???!!!

MC: Are the images on your porcelains all family members?

BL: The Good Children series started when I gave birth to my son, Tai, in 1987. I started thinking about how to raise a “good” person in this troubled world. So some of the early images in my work were loosely based on Tai as a little boy. As he grew older it seemed that the image of the child simply represented the qualities of childhood: innocence, potential, vulnerability and play. Additionally, the images of children invoke empathy and memory. I have made other pieces that are portraits of my parents such as in the Take Out Box stack, “I’m Migrant / Immigrant”. In the children’s books that I illustrated, Auntie Yang’s Great Soybean Picnic, and Mahjong All Day Long, there are loose portraits of several members of my family.

MC: Are your pieces autobiographical?

BL: Yes many of my pieces are autobiographical, or based on my emotions, opinions, and stories from the lives of my family members. Other subjects that I investigate through my work are my Asian American identity, parenting, legacy, inheritance, immigration, stereotypes, diversity, language and translation, food as culture, politics.

Mandarin Tricorne

Salem China Company, Salem, Ohio (1898-1967)

Don Schreckengost, designer Tricorne (American, 1911-2001), Vincent Broomhall, designer Streamline (American, 1906-1991), Herbert A. Smith, designer Streamline

Mandarin Orange on Streamline and Tricorne dinnerware, 1930s

semi-vitreous china, glazed

2014.198, 2019.174, 2020.282, 2014.157 Gifts of Margaret Carney and Bill Walker, Museum Purchases and Gifts of Victoria Matranga

Although designed in the early 1930s, Tricorne’s simple, modernistic shape and bright red-orange Mandarin color was a precursor to mid-century modern dinnerware designs that would follow a decade later.

Tricorne dinnerware was designed by Don Schreckengost for Salem China Company of Salem, Ohio. With consumer demand for color in ceramics, Don created the Tricorne plate shape in response to an innovative new orange glaze while he worked at Salem as a nineteen-year old college student on a summer internship with the firm. Tricorne was sold along with Salem’s Streamline shape, designed and patented in 1935 by Vincent Broomhall and Herbert A. Smith, which was used for accompanying vessels, such as the sugar bowl, creamer and cup in this set.

To market this dinnerware, Salem China Company partnered with Warner Brothers in order to associate their table wares with Hollywood glamour and celebrity. Its sales and marketing department hired movie stars to sit for publicity photographs taking their tea with the Tricorne and Streamline sets. Salem also collaborated with movie theatres on “Dish Nights” at which female moviegoers received a free piece of the brand’s china. These advertising schemes as well as Tricorne and Streamline’s aggressively modern color and pattern serve as reminders of the creative strategies that manufactures enacted to maintain a profit in the years of the Great Depression.

Donald Schreckengost was the brother of Viktor and Paul, all ceramicists, and all sons of a ceramicist from Sebring, Ohio. Don graduated from the Cleveland School of Art in 1935. While a student, in 1932 he worked at Salem China Company as an intern and then became their director of design. In 1936 he was awarded the Agnes Gund Scholarship to study sculpture under Adolph Jensen in Stockholm. From 1935 to 1945 he taught as a professor of ceramic industrial design at Alfred University, in Alfred, New York. He was the design director of the Homer Laughlin China Company in Newell, West Virginia, from 1945 to 1960. Following his tenure at Homer Laughlin, Schreckengost served as director of design for many pottery companies, including the Hall China Company in East Liverpool, Ohio, beginning in 1960; Mayer China Company in Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, from 1960 to 1963; Royal China Company in Sebring, Ohio, from 1962 to 1965; and Summitville Tile Company in Ohio, from 1969 to 2000. Don Schreckengost passed away in 2001.

Salem China Company was founded by Patrick and John McNicol, Daniel Cronin and William Smith in 1898 in Salem, Ohio. Originally producing commercial dinnerware and accessories, they shifted production to household dinnerware, novelty ware and souvenir plates. In 1918, the company was purchased by F. A. Sebring and Floyd W. McKee. By 1930, the pottery was firing 25,000 pieces per day and at the height of production employed over 500 people. Salem China stopped manufacturing wares in 1967 and was reorganized into a sales and service company.

References: Laurel Hollow Park Website, Webmaster: Mark Gonzalez (www.laurelhollowpark.net); The Official Price Guide to Pottery and Porcelain, 8th Edition, Harvey Duke (New York, NY: House of Collectibles, 1995); Cooper Hewitt Website (www.cooperhewitt.org).

essay by Scott A. Vermillion

LaGardo Tackett

Schmid Porcelain International

LaGardo Tackett, designer (American, 1911-1984)

Schmid Porcelain (International) Tack dinnerware set including coffee pot, teapot, expresso set, cream, sugar, 1950s

porcelain, glazed

2020.133 Gift of the Bill Stern Collection

Although the Schmid Porcelain green and orange dinnerware set in the IMoDD permanent collection is not marked with either “Kelco” or “Japan” backstamps, as are some similar pieces in other collections, one piece bears the apparent date “60” (“Schmid60 Porcelain Tack”). Perhaps these were prototypes for the Kelco dinnerware introduced sometime around 1960, that was produced by Schmid Kreglinger for the European and American markets, and designed by LaGardo Tackett. Schmid Kreglinger is a Japanese company and part of Schmid International, a Massachusetts-based importer and distributor of decorative wares.

With its clean, timeless design, this dinnerware line has been displayed in many international exhibitions and included in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Ceramic Art in Gifu, Japan as well as the International Museum of Dinnerware Design in Kingston, New York.

Designer LaGardo Tackett (nicknamed Tack) was born in Henderson, Kentucky in 1911 to Oscar and Lillian. Oscar was a grocer, and LaGardo’s unique name was taken from a tomato can in his father’s store.

Tack enrolled at Indiana University to study geology. He left after two years, but met his future wife and life-long collaborator, Virginia Lee Roth while at the school. In 1937, they moved to New York. Virginia worked for CUE Magazine, a New York events listing publication. Tack took a job at the May Company, the department store giant. In the 1940s, Tack was promoted as May’s interior promotion director, which required a move to hip Baldwin Hills Village within Los Angeles. While there, Tack attended classes at Claremont Graduate School and began working with ceramics. He also experimented with furniture design and won an award at the school’s annual student show.

After serving in World War II, Tack used the GI Bill to enroll in Scripps at the Claremont Colleges, which offered a formal academic approach to ceramics. There he took a keen interest in the evolution of cooking and eating utensils throughout history.

Tack taught classes at the California School of Art, including one course called Three Dimensional Design at his own kiln in Pasedena. During this period, he created many distinctive works and began mentoring talented students. In 1949, along with the works from several other ceramic artists, Tack’s and his student’s pottery was discovered by New York entrepreneurs, Max and Rita Lawrence, and marketed as Architectural Pottery. The Museum of Modern Art displayed Architectural Pottery in its 1951 Good Design show.

In 1952, the Tacketts had a modern house built in Malibu and in 1953 built a large ceramics studio in Santa Monica, where they called their business Tackett Associates. Their studio work was hands-on and hand-crafted.

They were introduced to Paul Schmid of Schmid International. The friendly and professional relationship that developed resulted in the Tacketts closing their studio and moving to Kyoto, Japan in 1956 to design full-time for Schmid.

Tack’s design work for Schmid International was prolific. Along with complete dinnerware sets, he designed many styles of serving pieces and unusual storage containers for condiments, coffee, tea, sugar, spices and other foods and kitchen necessities.

The Tacketts returned to Malibu for a while, but followed that with another move to Tokyo in 1960. In 1961, they returned to the United States and settled in Weston, Connecticut. They continued to work for Schmid International and commuted to New York for occasional meetings.

After their children were grown, Tack and Virginia made several more moves in the Connecticut area and they finally settled in New Haven, where they could work without a car and enjoy the local culture. Without a kiln or studio, he settled more into design theory. He explored the idea of the ever elusive perfect set of dinnerware that he referred to as “the 5 basic vessels.” Virginia passed away in 1982 and Tack in 1984.

References: “Discovering LaGardo Tackett,” F. Peter Swanson, M.D. (Connecticut Explored, inc, Winter 2010/11).

essay by Scott A. Vermillion

Kaye LaMoyne

Branchell Company, St. Louis, Missouri (1946-1958)

Kaye LaMoyne, designer (American,1918-1992)

Melmac FLYTE and Color-FLYTE and Royale dinnerware and flatware

Melmac, stainless steel

2020.88, 2020.261, 2020.102, 2020.72 Museum Purchases

2023.31 Gift of David Deutsch

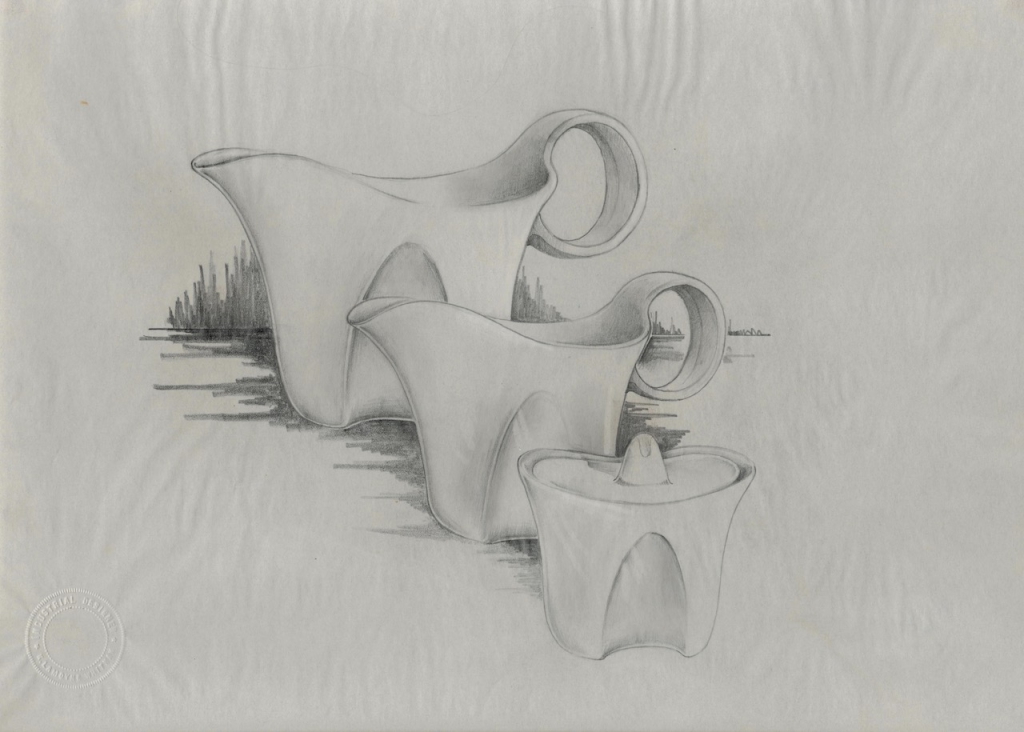

Kaye LaMoyne

Kaye LaMoyne, designer (American, 1918-1992)

original archival pencil drawing of melamine gravy, creamer, lidded sugar with blending stick shadings, and embossed signature

onion skin/tracing paper, pencil

mark: embossed stamp “K. LaMoyne Whitnah Industrial Designer”

Provenance: Estate of Kaye LaMoyne

2020.62 Gift of Scott Hamblen

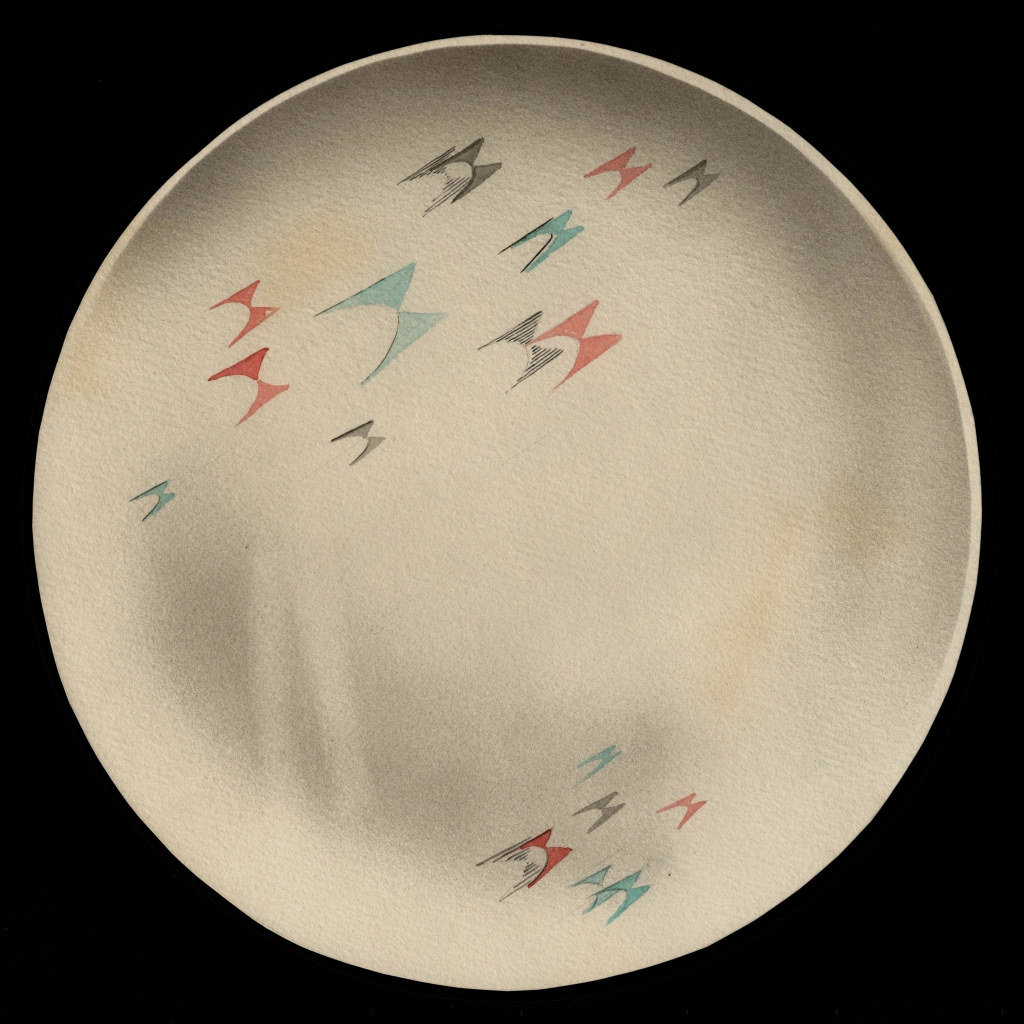

Kaye LaMoyne

Kaye LaMoyne, industrial designer (American, 1918-1992)

round plate shaped original pattern design for Branchell Melmac FLYTE dinnerware in pink, turquoise, and gray, unsigned and undated

paper, watercolors

Provenance: Estate of Kaye LaMoyne

2022.51 Gift of Scott Hamblen

Noted industrial designer Kaye LaMoyne was born Kaye Lamoyne Whitnah in 1918 in Topeka, Kansas. He studied design and color at an art school in Chicago. He worked as a freelance designer for Dunbar Glass in West Virginia. Later he moved to St. Louis, Missouri to become the sole designer for the Branchell Company until the founder of Branchell, Edward Hellmich, sold the company to Lenox in 1958. The heyday for melamine dinnerware was in the 1940s and 1950s, when there were dozens of companies manufacturing melamine.

The original design sketches included in the exhibition were created by Kaye LaMoyne and donated to IMoDD by Scott Hamblen.

In the 1950s he designed the highly successful Melmac lines Color-FLYTE and Royale for Branchell. This dinnerware was marketed in groups, and consumers were encouraged to mix and match the colors of the popular dinnerware. Before his death in 1992, LaMoyne had additionally worked as a freelance designer for North American Rockwell (aeroplane parts and interiors), Gaynor Sports Products (golf tools), designed golf courses, and designed spare parts for BMW Isetta. It should be noted that he was a golf enthusiast and he collected Isettas.

essay by Margaret Carney

Saenger Porcelain

Saenger Porcelain, Newark, Delaware

Peter Saenger, designer (American, b. 1948)

Design II “Captain Picard’s Tea Service,” 1990

2014.206 Gift of Margaret Carney and Bill Walker

An online interview with questions by Margaret Carney and responses from Peter Saenger in October 2024, resulted in this dialogue:

Margaret Carney: How did you first discover ceramics and your place as a contemporary artist/designer?

Peter Saenger: My path to contemporary tabletop design did not take the usual route …if there is such a thing. I started in as a potter making functional stoneware, designing work within the parameters of what was possible on a potter’s wheel. Ten years later, I had changed course; abandoning the wheel entirely, shifting my focus to a design-driven body of cast work. This shift necessitated learning new skills, teaching myself how to design in plaster, make molds, and cast clay. This transition was incremental, but it was clear that the contemporary craft audience was larger and more responsive to the design-focused pieces than it was to the wheel-thrown work. It is over this period of time that I became a designer.

First experiencing ceramics as an undergraduate in 1968, I was intrigued by the clay studio and the magic of the of potter’s wheel. Postgrad, after a stint of learning how to make pots six days a week at a Japanese pottery, I relocated to the States, built a kiln, and began making pots in a shared space. It was my great fortune to have ceramic artist, James S. Rothrock, working next to me in that space. Jim was a great resource- generously sharing his knowledge of casting, mold making, and porcelain.

Peg and I were lucky in our timing: contemporary craft galleries and fine arts & fine craft events were blossoming… and our pottery was growing along with them. After a handful of years, Peg left her day job; we now had two boys and a functional stoneware pottery business in a space large enough for us and a few additional artists. The markets supporting our work were the large weeklong craft fairs with days for gallery and shop buyers, followed by days open to the public. Exhibitor spaces at the best shows were highly competitive, and acceptance at the premiere shows was more miss than hit for us. With the aim to break through, we kept looking for new directions. I explored hand-building briefly, but quickly discovered casting and ceramic design was my thing, and is where I found my voice. Buyers always would ask, “what’s new?” Casting and ceramic design answered.

MC: Why do you create?

PS: In a single word, Joy. When I am creating I feel alive.

MC: How did you come up with the idea for my favorite tea set that Captain Picard also enjoys?

PS: How did I come up with the idea for the Captain Picard set?

The quipster in me answers – I wanted to make a tea set that’s together, really, really together.

Tea sets on trays, like the ones your Great Aunt had in silver, or even the ones I was making on the wheel in the early 1970s, were uninteresting in their presentation. To my eye those sets came across as disorganized groups of aloof individuals with an almost diva-like need for their own space on large, unwieldy trays. I wondered why anyone would want to carry that quivering armload… and I was curious if my new interest in casting could come up with a new take on the classic tea-set-on-a-tray idea.

The Captain Picard / Design II was the third attempt at the fit-together design of a pot and cups on a tray. Over the years I have completed at least fourteen variations on this theme. The composition begins on a tray with an assigned place for each piece. The pot and cups are committed in their relationship so that they appear to shape and shelter each other into a visual whole. Each piece must be reproduced exactly, the cups have to be identical, and interchangeable, the niches in the pot cannot vary in size or shape in order for the concept to work. The pot of the Design II Set nestles with the cups more intimately than early attempts. In my first attempt at this concept, the Tea Set, the handle-less cups back their little round rears towards shallow hollows in the pot. In the next iteration, the more sprawling Design I Set’s large mugs stand along side the pot on a larger tray. The problem solving of tabletop design is a complex puzzle of striking the right balance of the visual, tactile, and functional aspects of the individual pieces and then for the group as whole. The Picard Set’s pot flows around its four nestling cups in a compact composition which is easily carried on a manageable tray. The satin-glazed cups fit into the hand as well as they fit into the bespoke niches of the tea pot.

The Star Trek, the Next Generation connection came out of the blue, or, better said, out of deep space. Unbeknownst to us, someone gifted to the television show, a Design II Set, a Round Sugar Creamer on a Tray, and a Design II Mug Set. When a friend called excitedly reporting he had just seen our work on TV, our reaction was disbelief. It was quite some time before we learned that the generous donor was the owner of a gallery which represented our work and who was also a huge Trekkie. In numerous episodes spanning two original seasons and followed by decades of syndication, the Design II Set now lives on in eponomy as the Picard Tea Set.

MC: What other creative outlets do you enjoy?

PS: I enjoy working in the forest just outside my studio door. Improving biodiversity connects me to nature. Time spent editing what sprouts from the seed bed or planting and protecting native plants under the forest canopy, is time well spent.

MC: What questions do you ask yourself when designing tableware?

PS: In the beginning the questions are:

I wonder if I could…?

What happens if…?

Next comes the call and response of

Why is, or why isn’t, this idea working?

Repeat until the calls of “isn’t working” are silenced.

Viktor Schreckengost

Salem China Co., Salem, Ohio, (1898-1967)

Viktor Schreckengost (American, 1906-2008), designer

Free Form shape, Primitive pattern dinnerware, 1955

Semi-vitreous china, glazed with decals

2013.43-.47 Gifts of Virgene G. Schreckengost

2017.51 Gift of Megan Savransky

2017.52, 2020.20, 2020.21 Museum Purchases

Introduced in 1955 by the Salem China Company, Free Form was designed by Viktor Schreckengost and introduced his patented dripless cup with three feet that lifted the cup off its saucer. It was said in Salem marketing literature that “The feet… are neat! They won’t Drip, and they are Guaranteed for the life of the cup.” The Free Form teapot, creamer, sugar bowl, bowls, cruets and salt and pepper shakers were all designed with these distinctive feet that raised them off the table. All of these footed Free Form pieces were issued 5 US design patents on April 10, 1956 (patent numbers 177433-177437).

Although Metlox had already been using the name California Freeform for its own mid-century modern dinnerware, Salem was able to get a trademark for the name Free Form for this line of dinnerware with its abstract, sculptural shapes. As described in Salem advertising: “Free Form contains freshness and freedom of concept. There is not the repetition of obvious details to hold the set together, but an overall smoothness of simplicity, lightness and arrested motion. Each piece is an intriguing conversation piece. Each performs its function well.” In typical Salem fashion, the Free Form dinnerware line borrowed covered pitchers and casseroles from Schreckengost’s 1953 Constellation dinnerware line. Primitive was one of many patterns offered on the Free Form dinnerware shapes. It was described as being “Inspired by early cave drawings from southern France” and that “Little figures and deer romp and play all over the set.” Schreckengost designed this distinctive pattern in the hope that it would appeal to men. At the time of its introduction in 1955, the American kitchen was a woman’s domain… so despite its appeal today, Primitive had limited success.

Salem repurposed the Hopscotch Turquoise pattern for their North Star dinnerware line that they sold through their very successful grocery store continuity programs in the 1960s. These sales programs helped Salem survive the downturn in the US dinnerware business because of the onslaught of low-priced foreign competition.

Born in 1906, Viktor Schreckengost was the brother of Donald and Paul, all ceramicists, all sons of a ceramicist from Sebring, Ohio. Their father would bring home clay and other materials for the children to model. Every week he held a sculpture contest among the children, and the winner would accompany their father on a weekend trip into the local big city, Alliance, Ohio. Only years later did the Schreckengost children realize that their father systematically rotated the winner. Viktor graduated from the Cleveland School of the Arts (now the Cleveland Institute of Arts) in 1929. During this time he earned a partial scholarship to study at the Kunstgewerbeschule in Vienna. Viktor began designing for the Salem China Company in the mid-1930s, and in 1946 he was named their chief designer. In addition to designing for Salem, he designed pottery for Cowan Pottery, American Limoges, bicycles and pedal cars for the Murray Ohio Manufacturing Company. One of his best-known designs is the Jazz Bowl that he designed by special request for Eleanor Roosevelt while he was working for Cowan Pottery. Viktor founded the Cleveland Institute of Art’s industrial design program (the first of its kind in the United States) and taught design there for over fifty years. Viktor’s design style was highly modernistic, using an avant-garde aesthetic language and applying it to comprehensible forms and products. Viktor Schreckengost passed away in 2008 at the age of 101.

The Salem China Company was founded by Patrick and John McNicol, Daniel Cronin and William Smith in 1898 in Salem, Ohio. Originally producing commercial dinnerware and accessories, they shifted production to household dinnerware, novelty ware and souvenir plates. In 1918, the company was purchased by F. A. Sebring and Floyd W. McKee. By 1930, the pottery was firing 25,000 pieces per day and at the height of production employed over 500 people. Salem China stopped manufacturing wares in 1967 and was reorganized into a sales and service company.

References: Viktor Schreckengost: Designs In Dinnerware, Jo Cunningham (A Schiffer Book for Collectors, 2006); Mid-Century Modern Dinnerware: A Pictorial Guide, Michael Pratt (Schiffer Book for Collectors, 2003); Sears Archives, Wikipedia.; Viktor Schreckengost: American Da Vinci, Henry Adams, Ph.D. (Tide-mark Press Ltd., 2006), Salem Primitive Free Form Brochure (Salem China Company; Salem, Ohio, 1955).

essay by Scott A. Vermillion

Viktor Schreckengost

Viktor Schreckengost (American, 1906-2008)

design rendering: “Sketch for Compartment Tray Viktor Schreckengost,” signed,

undated, ca. 1930s

typed note taped to back: “Aeroplane Luncheon Tray of Semi-Porcelain”

20” x 30” on Monogram Illustration Board

L2021.10 On loan from the Schreckengost Family

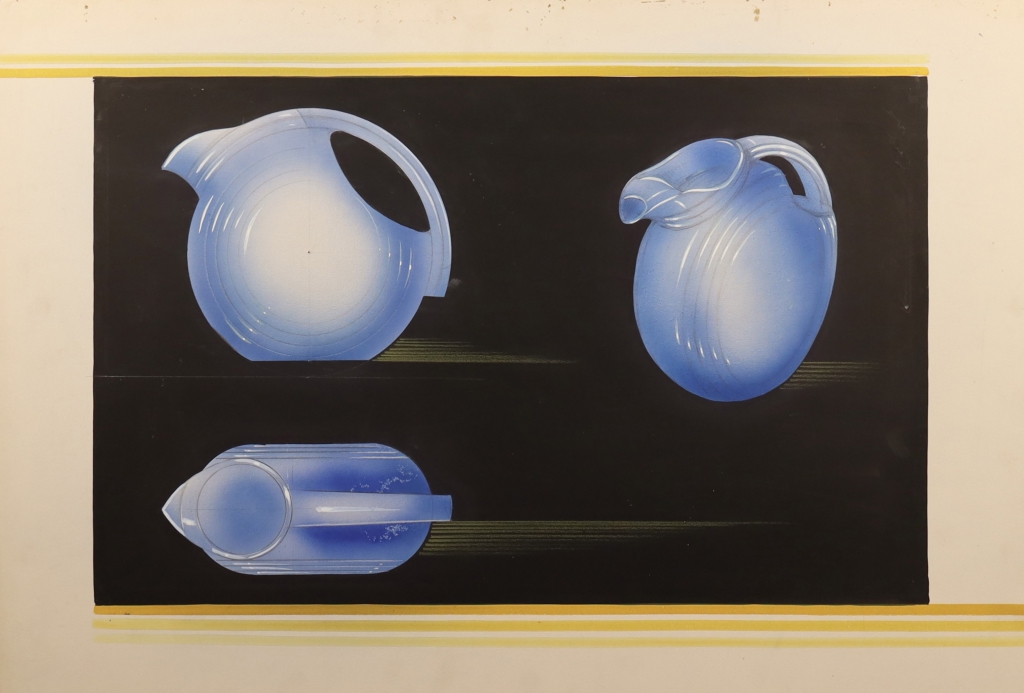

Viktor Schreckengost

Viktor Schreckengost (American, 1906-2008)

design rendering: three views of a pitcher in blue,

no signature, undated, ca. 1930s

20” x 30” on Monogram Illustration Board

L2021.3 On loan from the Schreckengost Family

Russel Wright Theme Formal

Yamato, Tajimi, Japan

Russel Wright, designer (American, 1904-1976)

Theme Formal coffee and tea pots, dinnerware, glassware 1965

porcelain, glazed and glass

2015.72 Gift of Mark Del Vecchio and Garth Clark

2021.54 (teapot) Museum Purchase

2022.48 (lidded casserole) Gift of John and Margarith Ashbury

Marketed together, Theme Formal and its casual counterpart Theme Informal, were Russel Wright’s ambitious concept for comprehensive formal and informal dinnerware lines with porcelain, stoneware, glassware, Bakelite lacquerware and wood serving accessories.

By the 1960s, the US dinnerware manufacturing industry had been decimated by less expensive imports from Japan and other countries. So for this line, Russel Wright turned to Japan’s Yamato Trading Company, which had been making porcelain and stoneware dinnerware since 1886. Schmid International, a Massachusetts-based importer and distributor of decorative wares, was contracted to import the line out of Japan. Raymor was responsible for distributing the line in the United States. Hemisphere Agencies in Japan distributed the line internationally.

Yamato Trading Company, Tajimi, Japan, (established 1886), Russel Wright, designer (American, 1904-1976), Theme Formal dinnerware including dinner plate, salad plate, bread plate, cup and saucer, platter, vegetable dish, side bowl, soup bowl, cereal bowl, coffee pot with lid, creamer, sugar bowl with lid, demitasse and saucer, beer glass, wine glass, water glass, cordial, 1965, porcelain, glazed, and glass, IMoDD 2015.72 Gift of Mark Del Vecchio and Garth Clark, Santa Fe, New Mexico

With high expectations for success, the forty-six-piece Theme dinnerware line was introduced at trade shows in 1965. Theme Formal porcelain was offered in white, and there have been some rare examples found with patterns. Theme Informal stoneware was offered in Dune, a mottled sand glaze with white flecks, and Ember, a dark black/brown glaze with orange flecks. Formal glassware was made of a white opaline glass and offered in four sizes. Informal glassware was offered in three sizes and in an amber color (and possibly other colors). Wood accessories were made of American elm. Bakelite lacquerware was offered in several colors.

Theme dinnerware was not well-received at the trade shows, and orders for the line were less than anticipated. As a consequence, Yamato did not commit to full production and what is available may have been limited to what was initially produced for the trade shows, to fill showrooms, and for anticipated first orders. Advertising evidence has been found showing that Theme dinnerware was available for a short time at retailers and discounted glassware was still being sold as late as 1967.

Theme Formal and Theme Informal were the last dinnerware lines that Russel Wright would design before closing his design studio in 1967 and retiring from full-time design work.

Russel Wright (1904-1976) is one of the most celebrated American industrial designers of the twentieth century. Born and raised in Lebanon, Ohio, while in high school, Wright would spend Saturdays studying at the Art Academy of Cincinnati with respected instructor Frank Duveneck. After high school, he studied at the Arts Student League and the Columbia School of Architecture, both in New York City. He continued his studies at Princeton University, where he was a member of the Princeton Triangle Club theatrical troupe. During this time, he won first and second Tiffany & Company prizes for outstanding war memorial sculpture. After graduating from Princeton, Wright returned to New York to start his career as a theater set designer.

In 1927, while working in summer stock in Woodstock, New York, Russel Wright met Mary Small Einstein, a designer, sculptor and businesswoman. They married and in 1930 opened a design office and formed the company Wright Accessories, where they produced useful and decorative objects for the home out of a converted coach house in New York City. Wright began designing furniture in 1934, which lead to the popular bleached “blonde” maple American Modern line for the Conant Ball Company

With a keen understanding of the importance of marketing, Russel and Mary Wright were some of the first designers to use their name on their products. With the introduction of his affordable, successful and groundbreaking American Modern dinnerware line in 1939, Russel and Mary Wright grew in importance as highly influential designers and tastemakers. Wright would continue designing dinnerware, art pottery, glassware, cutlery, furniture, lamps and other products and packaging into the 1950s and 1960s.

Russel Wright was one of the early members of the Society of Industrial Designers (later named the Industrial Design Society of America) and his work was often recognized with awards and in design exhibits at the Museum of Modern Art and other major museums.

References: Collector’s Encyclopedia of Russel Wright: Identification & Values, Third Edition by Ann Kerr (Collector Books, 2002) ); Industrial Designers Society of America Website (www.idsa.org).

essay by Scott A. Vermillion

Japan

Russel Wright, designer (American, 1904-1976)

Russel Wright designed in Japan, black with green lustre interior,

Theme Formal Shinko Shikki lacquer/bakelite covered rice bowl

lacquer/bakelite

2023.104 Museum Purchase

WASARA

WASARA, Japan (manufactured in China)

Shinichiro Ogata, designer (Japanese, b. 20th century)

15-piece sample kit WASARA biodegradable, compostable, tree-free, sustainable dinnerware, 2013 (initial design 2008)

sugar cane fibre, bamboo, reed pulp

2013.56 Museum Purchase