Ashtrays the Wright Way

[Link to Ashtray Page] [Link to How Ashtray became a dining story, by Margaret Carney]

Ashtrays the Wright Way!

Every design tells a story: the ashtrays of Russel and Mary Wright.

by Scott Vermillion

Before 1964, when the United States Surgeon General issued a landmark report linking smoking to serious health hazards—igniting public awareness and regulation—around 42-percent of American adults were regular smokers.[1] Today that number is closer to 11-percent.[2] And unlike today, when most public indoor smoking is prohibited, smoking indoors was once routine. Nearly every home, business, and vehicle had an ashtray, often several.

Ashtrays weren’t merely functional objects; they were a standard part of material culture. Restaurants branded them with logos, hotels put them on every nightstand, airlines built them into armrests, and automakers molded them into dashboards and rear doors. Homes often had a “good” ashtray for guests, just as they had good china. Even non-smokers owned ashtrays because it was assumed visitors would smoke.

For manufacturers, ashtrays were a perfect product: inexpensive, endlessly giftable, and ripe for stylistic expression. Pottery companies produced them in every glaze and shape imaginable. Metalworkers shaped them in a wide variety of metals, some enamel-coated. Glass companies made them heavy and faceted, signaling permanence and importance. Art Deco and mid-century designers treated them as modernist objects—biomorphic, atomic, sculptural. An ashtray could be promotional, decorative, or aspirational.

What’s striking in hindsight is how normalized smoking was—not merely tolerated but accommodated and designed for: ashtrays were part of everyday life. The dramatic drop in the percentage of people who smoke isn’t just a public health success; it explains why this entire category of everyday objects has virtually disappeared. In historical terms, ashtrays went from being essential household items to curios, collectibles, or repurposed catch-alls almost overnight.

Ashtrays are small artifacts, but they tell a big story about how people lived, gathered and shaped their surroundings, revealing how everyday habits—and the objects that supported them—can change within a single lifetime. For Russel and Mary Wright, as for so many Americans of their generation, ashtrays were once ordinary, ever-present parts of daily life, so familiar that nearly everyone carries a memory, or an “ashtray story,” of their own.

Few designers embodied the integration of lifestyle, design, and modern living more clearly than Russel and Mary Wright. Visionary collaborators, they revolutionized American home goods in the mid-20th century by making modern design accessible and affordable. Their products marked “Russel Wright” and “Mary Wright” are widely considered part of the first true lifestyle brand. Russel, an industrial designer, created thoughtful, organically shaped housewares for the modern home, while Mary Wright—a gifted artist and marketer—shaped her husband’s brand identity and public appeal. Together, their designs, made of metal, wood, ceramics, or combinations thereof, told a story about how Americans lived, gathered, and shaped their surroundings. Spanning dinnerware, textiles, furniture, and housewares—including the ashtray—their thoughtful design work reflected everyday habits and shared customs, transforming even small objects into vessels of cultural narrative and personal memory.

Like many people in the 1920s and 1930s, Russel and Mary were smokers. Cigarette use surged during this era, driven by advances in mass production and aggressive advertising that linked smoking as a symbol of glamour, modernity, and new freedoms for women,[3] along with celebrity endorsements, and inclusion in WWI rations. Social shifts during Prohibition and the Jazz Age further normalized the habit, all before the health risks were widely understood. Cigarettes came to symbolize freedom and a fast-paced, modern lifestyle, in contrast to older tobacco forms like pipes and cigars.

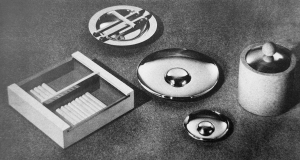

Annie Wright, their daughter, later recalled of her father that smoking “was part of his whole day.”[4] Given their personal familiarity with smoking rituals and their deep design expertise the Wrights were exceptionally well-positioned to create ashtrays that were both beautiful and highly functional (see Figures 1 and 2).

Russel Wright was born on April 3, 1904, into a prominent family in Lebanon, Ohio. His father, a lawyer like generations of Wright patriarchs before him, groomed Russel for Princeton University and a career in law. From an early age, however, Russel showed a strong interest in art, secretly keeping an easel in the attic—known only to his mother. She quietly allowed him to attend the Art Academy of Cincinnati while still in high school. Bright enough to graduate at sixteen but considered too young for Princeton, Russel instead spent a year in New York studying at the Art Students League. There, his instructors found his painting uneven but recognized a sculptural sensibility, encouraging him to transfer to the sculpture department—a shift that quickly brought recognition, including first- and second-place Tiffany prizes for a war memorial design.

At Princeton, Russel soon grew disenchanted with academic life but found creative fulfillment producing, directing, and designing costumes and stage sets for their renowned Triangle Show. As his commitment to art and theater deepened, he left Princeton before graduating and joined The Theatre Guild in New York, where he worked on Broadway and established a shop for producing stage properties. There, he began developing an aesthetic sensibility and interest in modern furniture and decorative arts that later found its match in Mary, his future wife and creative collaborator—laying the groundwork for his career as an industrial designer.[5]

Mary Small Einstein was born on December 13, 1904, into a well-to-do Manhattan family that owned ribbon and lace mills. Drawn to the arts, she studied sculpture with the avant-garde artist Alexander Archipenko, who served as an important mentor.[6] An education at the Ethical Culture School in Manhattan and at Cornell University, together with exposure to progressive European modernist ideas, provided Mary with the creative and intellectual grounding that would later complement Russel’s emerging design vision.[7]

Russel and Mary met in 1927 at the Maverick Festival in Woodstock, New York, an annual gathering of bohemian artists held at the Maverick Art Colony. Set in an open-air quarry, the colony was a utopian retreat where avant-garde theater, music, and art were celebrated. Russel had been recruited for theatrical set design and management, while Mary attended as Archipenko’s protégé, eager to study sculpture. Drawn to one another, they quickly fell in love and, despite objections by Mary’s parents, they eloped and married later that year.[8]

After their marriage, Russel shifted his focus from stage design to the emerging field of industrial design. Mary played a central role in their newly formed business, Russel Wright Inc., overseeing promotion, branding, and strategy while also contributing her own designs. Their earliest collaborations included one-of-a-kind or limited-run decorative accessories—ashtrays, cigarette boxes, and match holders—crafted from chrome (see Figure 3), pewter, brass, copper, aluminum, and leather (see Figure 4), often with ceramic, glass, or cork inserts (see Figure 5).

The Wrights’ early designs reflected a refined simplicity shaped in part by their exposure and understanding of European modernism. During trips to Germany in 1935 and 1937 (see Figure 6), they visited studios associated with the modernist art movement, including several connected to the Bauhaus, which had closed in 1933. Among the objects they brought home was a brass ashtray by Hayno Focken, an eminent German metal artist trained at the Burg Giebichenstein University of Art and Design. A concave brass circle with a subtly convex center, the ashtray embodied Bauhaus principles of functional elegance and understated form (see Figure 7). Russel kept and used it for the rest of his life, [9] and some of the Wrights’ earliest ashtray designs, influenced by the same ideas, closely resemble it (see Figure 8).

Reflecting on their early years in Industrial Design magazine, Russel recalled:

“In 1929, I doubt that there were a dozen people in New York who wanted to become practitioners of ‘Modern Design.’ … Most of us knew nothing of the roots of the theories which were being developed in Europe, but we were fired with the dream of redesigning everything for the world around us.”[10]

As demand for their designs grew, the Wrights not only expanded production but also broadened their offerings, marketing a comprehensive product line under the newly rebranded Wright Accessories Inc. By 1935, they established Russel Wright Associates to meet rising design and business demands—an expansion made possible by Russel’s growing reputation and Mary’s hands-on management of marketing and manufacturing.[11] Ashtrays and smoking accessories, a signature of their earliest design work, continued to play a key role in their product line.

In 1939, Wright introduced his iconic American Modern dinnerware line, manufactured by the Steubenville Pottery Company. Its open stock concept, modern organic shapes, and unique glaze treatments revolutionized the American table, making it one of the best-selling dinnerware lines of its era, celebrated for both style and practicality. Much of what made American Modern so popular was its thoughtful versatility. The line included a dual-purpose coaster that also served as an ashtray, and a later addition—the coffee cup cover—was designed to keep coffee hot (Russel liked his coffee hot)[12] while also functioning as a saucer or an individual ashtray for an after-dinner smoke (see Figure 9).

In 1940, Russel launched the ambitious American Way program, uniting more than sixty American designers and manufacturers to create affordable modern home goods. Ashtrays were well-represented, including designs by Robert Gruen, Mizi Otten, and Joseph Platt.[13] Despite a high-profile opening at Macy’s by Eleanor Roosevelt,[14] the program ultimately failed due to distribution challenges and the onset of World War II.

The postwar years were among the most productive for the Wrights. In 1945, while Mary was developing her Country Garden dinnerware line with Bauer Pottery in Atlanta, the company invited Russel to design a line of art pottery. The result was a striking collection of twenty vases, bowls and ashtrays with modern, organic forms in heavy clay, finished with earthy, mottled, and dripping glazes. Together, they reflected Russel’s strong sense of form and color, guided by a clear understanding of function.

Among the ashtrays, there were three smaller designs: Bauer #8A with a pinched end—a clever detail perfect for holding a single cigarette or a matchbook; #8B with a folded side; and #10A a rounded square shape. Bauer #17A, flat and egg-shaped, was marketed both as a bulb bowl and a large ashtray (see Figure 10). Annie Wright recalled that her father often used this larger bowl for smoking.[15]

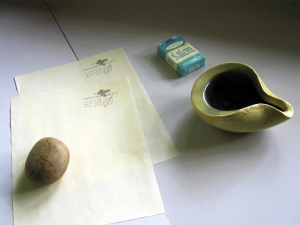

Today, Manitoga / The Russel Wright Design Center—the Wrights’ home, studio and woodland garden in Garrison, New York—displays a Bauer #8A pinched ashtray alongside Russel’s preferred Salem cigarettes, a small but evocative reminder of the designer’s daily life and enduring attention to functional elegance (see Figure 11).

Mary’s Bauer Country Garden dinnerware line, described as “freshly modern” and “superlatively handsome,”[16]included several pieces that could be used as ashtrays. A three-compartment, rectangular dish did triple-duty: designed to hold small butter pats with a sliding butter-plateau lid, it could also be used as a relish dish or an after-dinner ash tray. A flat, round relish with a playful S-shaped divider could be repurposed as an ashtray (see Fig. 12).

Following the tremendous success of American Modern, Russel Wright designed the Casual China dinnerware line for the Iroquois China Company in 1946. Advertised as “a multi-purpose china” with “modern styling”[17] the line enjoyed comparable success. Although Casual China did not include an ashtray—or even a coaster that could double as one—in 1952, Iroquois issued a promotional “Season’s Greetings” ashtray to advertise Wright’s dinnerware. It is unlikely that Russel designed the ashtray form itself; however, his deep affection for Christmas likely influenced his decision to approve and supported the promotion.[18] The charming “WARRANTIED AGAINST BREAKAGE” illustration—depicting a dapper, top-hat-adorned gentleman juggling pieces of Casual China—was almost certainly drawn by James Kingsland, one of Russel’s design employees, working under the direction of the Wrights (see Figure 13).

Kingsland was also the talented artist responsible for the modern, informative drawings featured in the Wrights’ groundbreaking housekeeping and lifestyle book Guide to Easier Living, first published in 1950. In the book’s “Equipment List for Entertaining,” the Wrights addressed essential ashtray types and their use in detail. For seated meals, they recommended covered ashtrays— “the smallest you can find, with a concealed chamber for ashes and butts.” For buffet service they suggested “small ash trays, an auxiliary supply, for example, dime store glass furniture casters” and silent butlers in unpainted metal. To further reduce maintenance, they advised: “To cut down on trips to empty ashtrays, use a large silent butler.” [19]

In their guidebook and in several newspaper articles, Russel Wright advised selecting furniture with finishes that resist cigarette burns. On the all-steel Samson folding chair, he designed for Shwayder Brothers Corporation (now Samsonite) in 1949, he promoted its sturdy arms as being “wide enough to hold ashtrays or glasses.”[20]

Introduced in 1949, Russel Wright’s vitrified Sterling dinnerware line for the Sterling China Company was intended for both home and commercial use. It was his first dinnerware line to include a purpose-designed ashtray—an essential item for restaurants and other public venues at the time. Like all of Wright’s designs, the Sterling ashtray was innovative, functional and modern. Its softly-rounded form was generously sized to accommodate multiple smokers, and a cleverly-integrated slot was designed to hold a matchbook—an ingenious detail that doubled as discreet advertising for restaurants, hotels, and clubs (see Figure 14).

In 1965, Wright was commissioned to design both the interior and a vitrified Sterling China dinnerware service for the Shun Lee Dynasty Restaurant in New York City. For this project, he created a two-compartment, butterfly-shaped dish that could be used for sauces or, alternatively, as an ashtray. The butterfly’s “body” cleverly divided the dish, allowing it to hold two sauces or two cigarettes neatly in place (see Figure 14).

Russel Wright’s first use of pattern on dinnerware appeared in 1951 with his Harkerware White Clover line for The Harker Pottery Company. Inspired by the woodlands he had cultivated at his beloved Manitoga, Harkerware was “sprinkled with white clover” in an incised pattern with “a few lucky four-leaf clovers tucked in” for the user to find.[21] Each piece featured softly rolled edges, speckled glazes in four colors, and a contrasting white glaze on the bottom, top or lid. Although White Clover was well-received by the design community, high price points combined with inconsistent marketing and distribution resulted in slow sales. To reinvigorate the line, a beautifully designed ashtray—absent from the original release—was later introduced. Dual-purpose and highly functional, the ashtray featured two curvaceous rests to accommodate multiple smokers, or it could be repurposed as a nut dish (see Figure 15).[22]

Introduced in 1956 and produced by the Edwin M. Knowles China Company, Russel Wright Knowles Esquiredinnerware line debuted with twenty-one pieces in “fluid, elegant shapes” with a “textured satin glaze.”[23] While the initial release did not include an ashtray, most of the pieces were designed for versatile, multiple use. The line featured six nature-inspired patterns on a softly colored matte glazes: Grass, Queen Anne’s Lace, Seeds, Snowflower, Botanica,and Solar.

Due to challenges such as difficulty in photographing the line for catalog sales and durability issues with the satin glaze, Wright revisited the line. He introduced solid-colored and semi-gloss glazes, added new patterns, and allowed Knowles to sell the line through other distributors—including International China Company and Serv’ Elegance—with their names included on the backstamp. With styling in keeping with the rest of line, he designed an elegant, five-inch round ashtray featuring six subtle raised ridges to hold cigarettes in place. Exceptionally rare, these ashtrays have only been found in the Solar pattern (without a backstamp), and in the Serv’ Elegance Botanica pattern (with a backstamp). This ashtray represents the last known accessory designed expressly for smoking by Russel Wright (see Figure 16).

Sadly, Mary Wright passed away in 1952, leaving Russel to raise their daughter, Annie, on his own. In 1965, Russel closed Russel Wright Associates and retired to Manitoga—the property that he and Mary had purchased in 1942, and where they had built a modern home along the edge of an abandoned quarry in 1949. There, Russel devoted himself to his lifelong love of nature, carefully tending the spectacular woodlands he had cultivated across the once-nearly barren 75-acre grounds.

Like many people of their generation, both Russel and Mary were lifelong smokers. While Russel would never set the dining table with an ashtray, after meals he would inevitably bring one to the table to enjoy a cigarette. Over the years, he favored certain ashtrays—his egg-shaped Bauer bowl, one of the smaller Bauer ashtrays, or his cherished German Focken ashtray. For anyone who grew up around smokers in the mid-20th century, these little objects often carry memories of small, daily rituals, and Russel’s ashtrays were no exception.

There is one ashtray that Annie will never forget: a metal piece gifted by the parents of a middle-school classmate. Blue and speckled with snowflakes, it seemed almost at odds with her father’s usual sophisticated taste—so much so that it felt almost wrong. And yet Russel liked it, perhaps because its indentation cradled a cigarette perfectly. After he passed in 1976, Annie let the ashtray go, but she still cherishes the memory[24]—a small, tangible link to her father, and to the quiet moments and stories that even the humblest object can hold.

Endnotes

[1] Addiction—Surgeon General’s 1964 report: making smoking history, Harvard Health Publishing, Harvard Medical Schools, January 10, 2014.

[2] Overall Smoking Trends, American Lung Association Website, Page last updated May 30, 2024

[3] Role Models: Mixed messages for women; A social history of cigarette smoking and advertising, Virginia L Ernster, Phd, New York State Journal of Medicine, July 1985, p 335.

[4] From a Zoom interview with Annie Wright, November 18, 2025.

[5] Conversations with Annie Wright, January 2026; Collector’s Encyclopedia of Russel Wright—Third Edition, Ann Kerr, Collector Books/Schroeder Publishing Inc. (2002), pp 13-14; Russel Wright Translates America’s Furniture Traditions Into Clean Cut American Designs, Edith Weigle, Chicago Sunday Tribune, February 23, 1936, p 63.

[6] The Power of Two, Mary Einstein Wright & Russel Wright, Garrison, NY: Garrison Art Center. 2015. Retrieved October 28, 2021.

[7]“Mary Wright Dies; Author, Designer” The New York Times. Retrieved October 28, 2021. (subscription required)

[8] Russel and Mary Wright: Dragon Rock at Manitoga, Jennifer Golub, Princeton Architectural Press (2022), pp 11-17; Collector’s Encyclopedia of Russel Wright—Third Edition, Ann Kerr, Collector Books/Schroeder Publishing Inc. (2002), p 243.

[9] From a Zoom interview with Annie Wright, November 18, 2025.

[10] Collector’s Encyclopedia of Russel Wright Wright—Third Edition, Ann Kerr, Collector Books/Schroeder Publishing Inc. (2002)

[11] Collector’s Encyclopedia of Russel Wright Wright—Third Edition, Ann Kerr, Collector Books/Schroeder Publishing Inc. (2002), p 281.

[12] From a Zoom interview with Annie Wright, November 18, 2025.

[13] Collector’s Encyclopedia of Russel Wright Wright—Third Edition, Ann Kerr, Collector Books/Schroeder Publishing Inc. (2002), pp 273-280.

[14] Collector’s Encyclopedia of Russel Wright Wright—Third Edition, Ann Kerr, Collector Books/Schroeder Publishing Inc. (2002), p 273.

[15] From a Zoom interview with Annie Wright, November 18, 2025.

[16] Mary Wright’s “Country Garden,” advertisement, H. Coate & Company Department Store, The Winona Daily News (Minnesota), August 17, 1948, page 5.

[17] Russel Wright Casual China by Iroquois, Iroquois China Company brochure, Syracuse, New York, date unknown.

[18] From a Zoom interview with Annie Wright, November 18, 2025.

[19] Mary & Russel Wright’s Guide to Easier Living, Simon and Schuster, New York, Printed in the U. S. A. by Acwelton Corporation and Bound by American Book-Stratford Press, Copyright 1950, 1951, 1954, pp 157, 193-194.

[20] Samson All-Steel Folding Chairs, Advertisement for The Hecht Company, The Washington Daily News (Washington DC), April 4, 1950, p 48.

[21] Collector’s Encyclopedia of Russel Wright—Third Edition, White Clover brochure photograph, Ann Kerr, Collector Books/Schroeder Publishing Inc. (2002), p 180.

[22] King Size Ashtray; Genuine 1st Quality Harkerware by “Russel Wright” Ash Tray or Nut Dish…Retail Value $2.00. B&B bought all the factory had for this special sale. Only 89¢, B&B Supermarket Advertisement, The Tampa Tribune (Florida), January 26, 1956, p 11.

[23] Knowles Esquire Antique White brochure, The Edwin M. Knowles China Company, 1956.

[24] From a Zoom interview with Annie Wright, November 18, 2025.